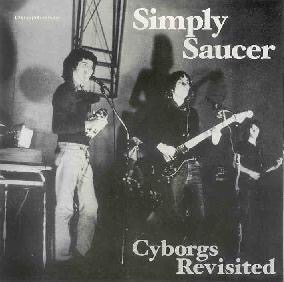

I’m due to hear from frontman Edgar Breau next week, so you might think it unusual not to delay TNPCs inclusion of Simply Saucer’s Cyborgs Revisited until after we speak. The thing is, I’ve constructed my own myth around this album, I’ve rewritten rock history in my head, and I’m reluctant to let it go, for surely if rock’n’roll is about anything, it’s about gratuitous escapism – so I’m going to hang on to this movie script for a little while longer…

“What a fantastic movie I’m in / what a fantastic scene I’m in…”

[Scene: Backstage, Velvet Underground performance, Max’s, August 22nd, 1970]

Any similarity to characters real or fictional is…blah blah blah…

DY: What’s the matter with you Lou – that was some hokey shit tonight?

LR: Cuz the whole thing’s fucked you asshole. Your stupid Cyborg obsession – it’s getting us nowhere. What the fuck is a Cyborg anyhow?

DY: Remember when you used to be rock’n’roll? Long time ago. You’re not even a footnote now. There’s stuff out there which is unbelievable Lou – wash out your ears, how can you not hear it? Look at the Ig guy – he’s insane. It’s just pure rock’n’roll…

LR: Let him go and do his shit. Who’s gonna remember that? They called it right. Stooges!! Just a noise goin’ fucking nowhere Doug…Forty people out there tonight...Brigid snapping away – who’s gonna want tapes of us playing this shithole?…

[SM (barely audible):hey…someone tell Jonathan to beat it…Jonathan get outta here man, go home…its late…]

DY: Are you outta your mind? It’s not like we’re reaching out Lou – nobody came then, nobody’s comin’ now, nothin’s changed; let’s face it. But til now, at least we’ve been able to hold our heads up man. You know, I’m beginning to think Cale got it right. He got out cuz he knew this lame loser shit was on the way…

LR: Hey, I got rid of that asshole… that’s precisely the kinda bullshit I might expect to hear from him!…I mean…avant garde, avant garde?! – thinks he’s John fucking Cage. One letter outta place in the name he thinks he’s a fucking genius. That one letter makes all the difference! He was never gonna be a star and neither are you Dougie boy. I’m a star, just like Andy says, and not for fifteen minutes either…just try to stop me honey.

DY: I didn’t join the band to become a star Lou. You want your face on a magazine cover, that’s your business – I want more. I want people to talk about my music 50 years from now.

LR: Your music!? What are you, some kinda comedian? What’ve you ever done? You’re just hanging on my coat-tails you asshole – just along for the ride! Playing supper clubs for twenty people ain’t gonna pay the bills. Well, what you gonna do after tomorrow, you’ll be on your own…cos it’s over…?

DY: Asshole!

LR: No, you’re the asshole…

Of course, as we all know, Lou walked out the very next evening, before Yule dragged Velvets’ devotee Jonathan Richman with him and they, together with a noisy young Rimbaudesque poet called Richard Meyers, went on to blitzkrieg the vacuous coked up pomposity of early 70s rawk, with all its ludes and bad hair and mind numbingly bland guitar solos, via their paradigm-shifting interstellar punk rock…

Or perhaps not… this is only a movie after all.

…In actual fact, Yule made Squeeze the ‘fifth’ VU album, which nobody recognises as an authentic release – it wasn’t of course, as it featured none of the original members. By 1974 he had done nothing else but add guitar to Reed’s Sally Can’t Dance. He would resurface again with the feckless country rock of American Flyer just as punk was exploding. It turned out Doug Yule was never going to do anything authentically punk. But it was not outwith the realm of possibility that he could have been the prescient saviour of rock’n’roll. After all, he joined the Velvets right after White Light White Heat. The last ‘song’ they recorded before he walked in the door was ‘Sister Ray’. If that didn’t put him off, then it was still a hell of a long way to slide before he got to writing ‘Dopey Joe’… so my guess is he must have possessed a tiny kernel of the punk gene, but he buried it. Somewhere deep. Unless of course, he was, as Lou says, just along for the ride…

So, instead it was left to some scraggy music & sci-fi obsessed teenagers from Ontario to pick up the mantle…their lives would be saved by rock’n’roll and they aimed to save it from annihilation along the way.

“I like the way that you treat me like dirt…”

Hamilton lies close to the Canadian/US border. The two US cities in closest proximity are Detroit and Cleveland – and if you’re looking for clues as to the origin of Simply Saucer’s sound, you need look no further. While the primary influence was undoubtedly The Velvets, Simply Saucer’s true kindred spirits were Iggy, MC5, Mirrors, Rocket From The Tombs and The Electric Eels, alongside a hearty dose of Krautrock and a psychedelic spattering of Syd’s Pink Floyd and Hawkwind.

The band – Edgar Breau (guitar, vocals), Kevin Christoff (bass, vocals) John LaPlante – aka Ping Romany (electronics) and Neil De Merchant (drums) would hardly become household names; formed in 1973, they only ever released one single (in 1978) before quietly disbanding. It would take another ten years before an album collection finally emerged. Culled from only two sessions – one recorded in Bob and Daniel Lanois’ mother’s home in 1974, the other recorded live in Hamilton a year later – Cyborgs Revisited was the first full length document of their incredible music, and as such is one of the great lost albums of the 70s.

A virulent distillation of acid-fried space rock and brutal urban punk, it comes over as a deranged masterpiece. ‘Instant Pleasure’ possesses the shambolic jerk of the Neon Boys’ ‘Love Comes In Spurts’ although predates it. As Breau pleads “Let me sleep inside of your cage / I want to feel your sexual rage”, Christoff’s impossibly spasmodic bass convulses around Romany’s anarchic theremin noodlings. ‘Electro Rock’s garage riff could be something off MC5s High Time. Delivered in Breau’s slovenly sneer it is laid to waste by a collision of screeching guitar, pummelling bass and some bizarre electro-magnetic loops. ‘Nazi Apocalypse’ degenerates magnificently into a big Ron Asheton wah-wah scorched earth guitar storm and the instrumental ‘Mole Machine’ is like a psychic summons to outer space by a college of math rock guitar freaks beckoning with all their might (and incomprehensible formulae) the descent of the mothership…it succumbs gladly to their invocation.

On ‘Bullet Proof Nothing’ Breau does indeed does sound like Yule having a crack at ‘Sweet Jane’ with The Modern Lovers providing the back up. (“Treat me like dirt, drive me insane / treat me like dirt now, tear out my brain… I’m just bullet proof nothing to you / Point blank target for your waves of abuse.”) Despite the nihilistic sentiment, it’s the most accessible thing on here, and would have fitted comfortably onto Loaded or even Transformer and even ennobled both of them. At any rate it truly is one of the great lost tracks of the 70s.

But it is no exaggeration to say that the live tracks (which comprise Side Two of the album) – recorded on a roof on Jackson Square on June 28th 1975 are just staggering – a revelation. The live version of ‘Here Come The Cyborgs’ is an astonishing sonic assault with more killer guitar riffs than James Williamson could accumulate on the entire Kill City LP. And that’s saying something. It briefly melts down into a blues jam and then knocks satellites out of the sky before the discordant thrash at the tail – a precursor to The Fall’s ‘Hip Priest’. Meanwhile, ‘Dance The Mutation’ is like a Jumpin’ Jack Flash Jagger cranking it out over an unstoppable tidal wave of nuclear moog radiation from Romany which evidently hungers to swallow up everything in its path. And as for ‘Illegal Bodies’ well, it captures on tape one of the most viscerally exhilarating guitar performances ever recorded. Think for one moment of ‘Run Run Run’ – it’s a smack song right? Well, ‘Illegal Bodies’ has that guitar, but Breau propels the song forward with such amphetamine fuelled momentum that, cut loose from its moorings, it spills its guts out all over the place…a sprawling mess of sheer punk adrenalin.

Now imagine if Breau, Romany and co had been afforded proper exposure at the time. Surely rock history would have been rewritten and perhaps punk would never have happened at all. There would have been no need. Julian Cope wrote a genius review of it on his Head Heritage site around 15 years ago – it’s here (https://www.headheritage.co.uk/unsung/albumofthemonth/simply-saucer-cybords-revisited) and no-one has came close to it since, so there may be a chance you’ve tracked it down before now, but if it’s something you haven’t heard yet, then I envy you your first listen. This is the stuff you’ve been looking for. (JJ)