RANDY NEWMAN – RANDY NEWMAN (1968)

My introduction to Randy Newman came even earlier than I realised. It was 1974, I was five and I was a few green months into primary school. Before the ruthlessly efficient, stripped-and-stranded TV scheduling of today, unforseen gaps would on occasion appear between programmes, in the grand interlude tradition of the potter’s wheel and the kitten frolicking.

One such hole was plugged by a cartoon accompanying a song which told the commonplace story of a couple travelling through life. I hardly knew anything of such matters at the time but it appeared straightforward enough: meeting; marrying; having children. Only the last line of the song stuck but it haunted me for years: as I recalled, it was a female voice singing: “We’ll play checkers all day/until we pass away,” as the now elderly couple vanish from either side of the board. It may well have been the first time I gave any thought to mortality, so strange and sad did I find it.

Scene fades…it’s now 14 February 1988. Without the remotest prospect of getting a card, it’s just another day for 19-year-old me but, it being a Sunday, Annie Nightingale is on and she’s doing a Valentine’s Day special, in which every song played includes the word ‘love’ in the title and is one more display of the sheer unpredictability of her show which reached its apogee the night she played Duran Duran and immediately followed them with Bogshed . I hear what are by now the familiar tones of Randy Newman – droll, drawling, dry – clothed in sumptuous orchestration which gives way to a similarly lush chorus echoing Spector with precision. Hints of Dixie jazz, hints of minstrel tunes – and then that lifelong game of draughts again. Love Story by Randy Newman – first part of the mystery solved.

It would take the internet’s reduction of total mysteries to double figures before the puzzle would be complete. The first version I heard, complete with animation, turned out to be by Sonny and Cher – they’d performed it for their own show, even as it was rapidly losing autobiographical status for them.

And Love Story turned out to be the opener of Newman’s debut album. Even in 1968, its subtitle – Randy Newman Creates Something New Under The Sun – must have seemed a shade brazen. Though decades would pass before all the possibilities of Popular Music were finally exhausted, there was already an end-of-history mood prevailing. Psychedelia and its attendant adventures far from rock ‘n’ roll’s roots were already being dismissed by many – and still are to this day – as an aberration. Practically every leading figure released something that year which, while ranking among their best, was again holding fast to Earth rather than exploring further into space, even as the first lunar footfalls approached fast (years later, in his soundtrack for Apollo documentary For All Mankind, Brian Eno would explore the paradox of astronauts listening to country – one of the most Earthbound of all genres – as they ploughed through the vastness).

But like The Band, and to some extent Bob Dylan, Newman was digging back further still. Not quite as far as The Band’s evocations of the Civil War but to the first third of the 20th century, a superficially genteel land of barbershop quartets, rocking chairs on antebellum porches and straw boaters tipped to every passing parasol-twirling dame, all the stranger for being well within living memory yet utterly bygone. He was steeped in this stuff, with with three composer uncles whose credits stretched from Modern Times, The Grapes Of Wrath and The Best Years Of Our Lives to Cleopatra and Alien. Characteristically, he embraced his heritage but with more than enough guile, bile and style to find favour with the burgeoning Serious Rock audience. As a practitioner of the now thoroughly debased (with a few exceptions, trite, wheedling and spectacularly point-missing in the 21st century) singer-songwriter genre, Dylan comparisons came like death and taxes…but listen to him singing “so hard” on Living Without You and then Boaby’s “so bad” and “so sad” on One Of Us Must Know and it’s valid for a moment at least.

And they’re both controversial voices. Add them to a long list – Ray Davies, Neil Young, Bryan Ferry, Robert Wyatt, Joanna Newsom, Anthony Hegarty; in fact, the oft-told story about Newman’s debut is that Reprise felt compelled to advertise the album with the somewhat backhanded tag “Once you get used to it, his voice is really something” but in vain – low sales followed. True, Newman does usually sound like he’s never more than a few seconds away from making a wisecrack about your choice of shirt but he sounds genuinely wounded on the aforementioned Living Without You, while the sauntering melodic nonchalance of Bet No One Ever Hurt This Bad belies what seems to be real sorrow – or is it one of the double bluffs which Newman tosses up to keep us on our toes? (see also: Rednecks, which satirises not only the racists but also the smug superiority that wealthy, educated types feel towards them; Mr Sheep, which mocks not the office drone but the arrogant rock star sneering at the office drone, and, most notoriously, Short People, which was proven to be a masterclass in genuine irony by its mass misinterpretation). Maybe they can just be taken at face value after all – I’m not aware of him having done his own version of I Don’t Want To Hear It Anymore but Dusty Springfield’s interpretation reaches Great Pumpkin levels of sincerity. When Newman sings, though, he just keeps you guessing; the son in So Long Dad seems as devoted as he needs to be but is still impatient and in a hurry (“Just drop by when it’s convenient to/Be sure and call before you do”) yet its mirror image, Old Man (on 1972’s Sail Away) ends with as devastating a line as you’ll find anywhere – “Don’t cry old man, don’t cry/Everybody dies.”

Another likely consequence of the divisiveness of Newman’s voice is that

many of his songs have become better known through versions by others but few of these have improved on his. One of the best known covers is Three Dog Night’s version of Mama Told Me Not To Come, from 1970’s 12 Songs. Newman is said to have observed that they gave it a chorus he never did but I’ve always found their attempt pretty awful – I’m usually a sucker for electric piano but theirs is a smarmy burble and that chorus is in the type of hammy, overwrought voices which were all too prevalent at the time. They also had a stab at Cowboy, which is on Newman’s first album – it’s more tolerable but again, he triumphs easily – the verses are sotto voce but the arrival of the orchestra for the chorus is truly startling, batwing doors not so much flung open as breached with a battering ram.

With Newman’s own arrangement and the deft production of stalwarts Lenny Waronker and Van Dyke Parks, it’s the sort of thing John Ford might have commissioned (commanded?) for one last bold sweep of Monument Valley before the credits roll. The lyrics, though, reflect more a Sam Peckinpah vision of a landscape changing too rapidly for its inhabitants to keep up with (“Cold grey buildings where a hill should be/Steel and concrete closing in on me.”) It was a reality for many as alleged progress rode roughshod over communities – Family offered a British perspective on the same theme later the same year with Hometown.

I Think He’s Hiding is one of Newman’s numerous meditations on the nature, attitude and, ultimately, existence of God. Here, he offers the view of those who believe in both a merciful (“There’ll be no more teardrops/There’ll be no more sorrow”) and a vengeful (“When the Big Boy brings his fiery furnace/Will He like what He sees/Or will He strike the fire and burn us?”) deity before hedging his own bets to a hushed and subdued accompaniment. Even more minimal is I Think It’s Going To Rain Today, which has become possibly Newman’s most covered song – maybe because it’s so spare that there’s a widely felt need to embellish it. There’d be a decent album to be had from compiling the best versions but Newman’s would have to be among them – you strain to hear him whisper (even Leonard Cohen took 20 years to reach this depth of register) and when you catch what he says, it still seems densely enigmatic (“Scarecrows dressed in the latest styles/ With frozen smiles to chase love away). In its strange invocation of solitude in a sparse landscape, like many songs here it’s unequivocally American but deals in universal themes, in style as finely etched as a Whistler and in content as acutely observed as an Edward Hopper – and the whole album packed with these brilliantly crafted miniatures is over in under 28 minutes.

Newman seems so unassuming on the cover; in houndstooth jacket and yellow turtleneck, and minus the curls and glasses which would later be his visual trademark, he could almost be mistaken for Neil Sedaka. There’s no more sign of him as the unofficial biographer of human foibles than there is in some of his more recent, far better known activities. To many, he is just Toy Story Guy, and that’s fine – there aren’t many films that offer more sheer joy (though for what it’s worth, I actually prefer Toy Story 2) but there’s a further frisson to be gained from the knowledge that he could also write (from Laughing Boy): “Find a clown and grind him down/He may just be laughing at you/An unprincipled and uncommitted clown/Can hardly be permitted to/Sit around and laugh at what/The decent people try to do.” (PG)

Author: tejopa

70. ANNETTE PEACOCK – I’M THE ONE (1972)

Cover versions are more often than not a waste of time, but not always. The best recorded versions of ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ and

‘Love Me Tender’ are not by Elvis Presley, but by John Cale and Annette Peacock respectively. Cale recognised the potential for a sonic overhaul of Mae Boren Axton & Tommy Durden’s classic, in order to provide a more suitably unsettling backdrop to the familiar tragic narrative. Similarly, with ‘Love Me Tender’, Peacock was able to excavate the cracks and crevices of that yawning cave to extract from it every ounce of emotional nectar, every last drop of raw-nerved soul. Hers is one of the most striking cover versions ever recorded and one of the highlights on I’m The One, her first official solo album released in 1972.

In addition to being a great interpreter of others’ songs, Annette Peacock is also a true innovator. I first heard ‘I’m The One’ around 25 years ago. I had given one of my TNPC colleagues a loan of Tim Buckley’s Starsailor LP, and in return he had alerted me to Annette’s solo debut. Comparisons have sometimes been made between the two. However, unlike Buckley, who reputedly eschewed any electronic augmentation of his voice on Starsailor, Peacock was unafraid to embrace new technologies – she had already written, performed and recorded experimental music with the late free jazz pianist Paul Bley in the late 1960s (including a showcase performance at the Lincoln Centre, NYC) and was keen to explore the possibilities of processing her voice through a Moog synthesiser. The story of her acquisition of this equipment and it’s incorporation into the recording of ‘I’m The One’ has been documented elsewhere, including in a brilliantly insightful interview with Annette in The Quietus – see below:

(http://thequietus.com/articles/15423-annette-peacock-interview)

The results were sensational. What I heard then astonished me. Even though the album was almost 20 years old, I felt immediately transported 50 years into the future, as if I was suddenly creeping through a smoky jazz bar in a sparsely populated embryonic human settlement on a Martian plain. A slinky, incredibly hip android fixed me with her gaze. From behind a stack of strange electronic equipment, she sang her visionary take on the blues.

Today, in a world of vapid auto tune and essentially formulaic stylised X-Factor singing, which follows a peculiar trajectory from Stevie Wonder through Mariah Carey and Alicia Keys, and which often values technical virtuosity above authentic soulfulness, how refreshing it is to hear something both at once so earthy, rooted firmly in jazz and blues, yet at the same time wildly unconventional and truly original. Peacock’s musical ethos was simply to sound as contemporary as possible, not to be wilfully obscurant or self-consciously avant-garde, but as a consequence of her enthusiasm to explore and innovate it is only now that I’m The One is getting some long overdue recognition. The world it seems is still catching up.

From the Sun Ra-esque introduction featuring a startling vocal ascent through the scales, Peacock rips through the material, a vivacious blend of avant-garde jazz, funk, blues and soul (‘One Way’ has the lot: space age jazz, swinging cabaret, squawking horns, Annette’s wild shrieking and not least, Tom Cosgrove’s formidable coiled guitar)

On ‘Pony’ the voice processing is integrated so smoothly that it sounds akin to some of Miles’ horn squeezing from On The Corner. Here the electronics bubble and fizz, as if Alan Ravenstine from Pere Ubu has been let loose to roam the stoned corridors of a Curtis Mayfield blaxploitation groove. It’s one of the coolest, funkiest things you’ll ever hear. ‘Blood’s improvisational synth rumblings are darker, befitting Annette’s anguished delivery, but give way to Bley’s more bluesy (almost Touissaint-y) piano at the finale.

But it is the title track itself which best encapsulates Peacock’s vision. I’m trying hard to imagine what this must have sounded like in 1971 when it was recorded. This would have been around the same time as What’s Going On, Hunky Dory’ etc. Indeed David Bowie was so taken with it, that, a year or so afterwards, he attempted to entice Peacock to contribute to his work in progress, Aladdin Sane. She refused. What sounds initially like a cerebral intergalactic conference becomes a red-blooded alien seduction – a lusty and libidinous Venus flytrap [I’m the one,/I’m the one/You don’t have to look any further/I’m the one/…I’m here, right here, for you/Can’t you see it in my eyes/Can’t you hear it in my voice/Can’t you feel it in my skin/When you’re buried deep within me/I’m the one for you‘]

Laurie Anderson, Eno and Bjork are amongst many who succumbed to the spell. Peacock would go on to deliver a follow up of equally intense and frank eroticism (X–Dreams). That one featured an all-star cast including Mick Ronson, Chris Spedding and Bill Bruford. But little of what was happening in 1971 compares to the power and glory on display here. This my friend, is the one. (JJ)

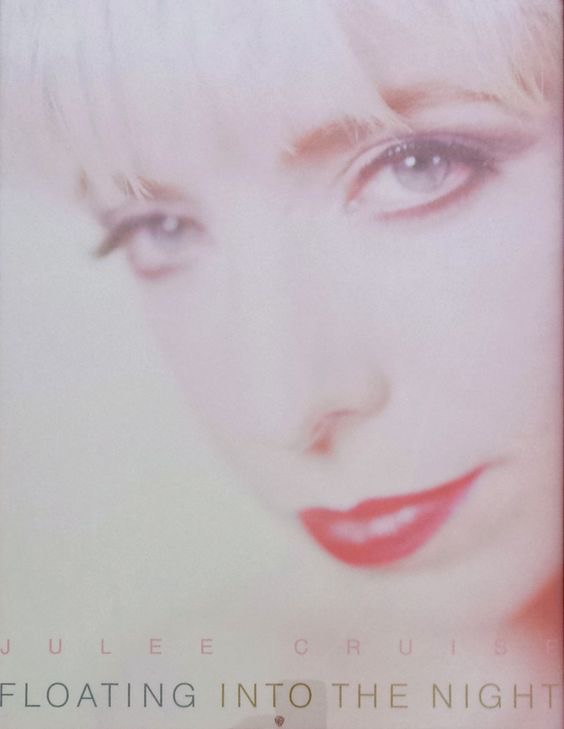

69. JULEE CRUISE – FLOATING INTO THE NIGHT (1989)

I recall during a particularly acrimonious musical discussion, eliciting an incredulous response when I compared Julee Cruise’s ‘Floating Into The Night’ to Captain Beefheart’s ‘Trout Mask Replica’. Stay with me here… This isn’t one of those ‘odd one out’ rounds on ‘Have I Got News For You’. Neither does it originate from the excruciatingly uninteresting fact that both albums are permanent fixtures in my all-time top ten, for by that criterion alone, ‘Trout Mask Replica’ would rather absurdly, have less in common with ‘Safe As Milk’ than it does with ‘Floating Into The Night’. So what might the two possibly share in common? It may be harder to imagine two albums which sound so completely different, that are so utterly incongruous: one a primitive, abrasive, angular, chaotic cacophony; the other one whispers it’s cotton wool lullabies so bashfully that it almost isn’t there at all. Indeed one might take the latter as a medicinal antidote after swallowing too much of the former. Playing the albums back to back may prove to be the ultimate aural speedball.

David Lynch. He might understand where I’m coming from. And not simply because ‘Trout Mask Replica’ is reputedly the great man’s very own favourite LP. That is not the answer to the puzzle either, although there is really no puzzle to solve. This isn’t ‘Mulholland Drive’. Here’s the deal. There are genuinely few albums I can think of which have ‘Floating Into The Night’s untainted singularity of mind. ‘Trans Europe Express’? For sure. ‘Ramones’? Without question. Perhaps only one or two others, ‘Trout Mask Replica’ for example. ‘Floating…‘ creates it’s own sound world, possesses it’s own authentically unique atmosphere and timbre, but ultimately, its genius lies in its economy and purity of vision. It stands oblivious to the world around it – like Buddha at the centre of the spinning wheel – and sounds completely at odds with the prevailing zeitgeist. It is also clearly the work of obsessive perfectionists. And that’s a description equally fitting of ‘Trout Mask Replica’.

Those obsessive perfectionists were of course Lynch himself and Angelo Badalamenti. The fruit of their first collaboration was the soundtrack to ‘Blue Velvet‘ which featured ‘Mysteries Of Love’ by the then largely unknown singer Julee Cruise. The timbre of that song – in common with other Lynch soundtracks, hinted at the existence of a dark underbelly beneath the respectable wholesome veneer of small town America. But it is an even earlier Lynchian incarnation which provides a clearer indication of what he intended to accomplish more fully on ‘FITN’: in the 1976 experimental film ‘Eraserhead’, a petite woman with a bizarre facial deformity sings a song – the song is ‘In Heaven Everything Is Fine’. It is also known as ‘The Lady In The Radiator Song’, and is the archetype for the ballads Julee Cruise would sing so beautifully on ‘FITN.’ Of course by 1988-89, Lynch was working on the ‘Twin Peaks’ project (film and TV series) which yielded as it’s main theme ‘Falling’ also included on ‘FITN’. Lynch’s genius as a director has been to match beautifully unsettling images with gorgeously transcendent music, the innocence of which is instantly perverted by disturbing visual accompaniment. His capacity to surprise viewer and listener by uncovering the more sinister dreams and desires in human nature is what makes his work so distinctive. As a consequence, the unspoken fear that all may not be well hangs like a pall throughout this recording too.

This is not a record characterised by passionate performances; Cruise’s gentle but bewitching delivery alongside it’s phantasmagorical little brushes with doo-wop (the wonderful ‘Rockin’ Back Inside My Heart’) and rockabilly could almost sound ironic. There not. One senses the record’s grooves like human veins have been invaded, each drop of its blood extracted, sacrificed. On only two occasions (‘I Remember’ and ‘Into The Night’) is there an unexpected twist (a disarming little change of tempo), or anything overtly soulful in the musicianship (a blast or two of brass). Elsewhere the music is characterised by an almost stoic reverie, but underneath, always an air of unease, uncertainty. The penultimate track ‘The Swan’ typifies this. Over Badalamenti’s achingly hypnotic melody, Julee’s enchantingly mysterious vocal is mournful, almost funereal. [‘You made the tears of love /Flow like they did when I saw /The dying swan…Then your smile died/On the water/It was only a reflection/Dying with the swan’]

Best of all is ‘The World Spins’ – the solemn eternal slow motion circular dance of the Universe unfolding. We gaze at the stars. What little we see of life’s mystery has become fleetingly clear, but angels are weeping for who knows what tomorrow might bring. But for this moment at least, on this, the last day of another year, everything is fine. (JJ)

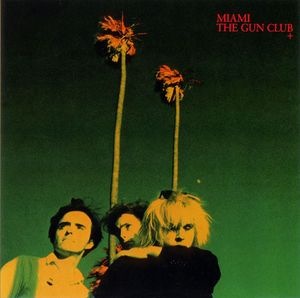

68. THE GUN CLUB – MIAMI (1982)

Jeffrey Lee Pierce in bona fide rock’n’roll tradition, was destined never to grow old. He barely gave himself a chance. The first diagnosis of cirrhosis of the liver may well have been as early as 1982. Pierce was a mere 24 years old then, two thirds of the way through his brief earthly sojourn. That he lasted as long as he did surprised some, but his death in 1996 (from a brain haemorrhage) still came as a shock to many. The Gun Club had made a career out of being the craziest, drunkest, most shambolic act on the LA scene. The band members played their parts willingly. After all, as Pierce said at the time: “People here have got nothing else to do but lose their minds.” Who better than Jeffrey to help them on their way?

When Pierce – who ran Blondie’s West Coast fan club – met Brian Tristan (Kid Congo Powers) – chief of The Ramones fan club – at a Pere Ubu gig in 1978, sparks were destined to fly. First baptised Creeping Ritual and soon after The Gun Club, this early incarnation were according to Powers “too arty for rock people, far too rock for arty people, too cuckoo for the blues crowd and too American for punk”. If history was theirs to make, it was near inevitable that their legendary status would be born of their scabrous and uncultivated live performances and their antagonistic personalities, rather than from their mercurial discography. The Gun Club would never neatly present us with a ‘Forever Changes’ or a ‘Marquee Moon’; their anarchic lifestyles possessed neither the patience nor prissiness for that to happen.

By rights there should be no place on this list for their second LP ‘Miami‘. Gun Club devotees, accustomed to the band’s cathartic early performances, lament the emasculated mix of an album which in the right hands, could have been a career defining, even generation defining moment. It wasn’t. A critical and commercial failure, it lacks the blood and guts of their debut ‘Fire Of Love’, the nocturnal glare of ‘The Las Vegas Story’ (Pierce’s personal favourite) and the polish and swagger of ‘Mother Juno’. At least the latter pair provided the most unpunctual of platforms for original member Kid Congo Powers, absent from the band’s early records on Cramps duty, and ‘Miami’ doesn’t feature him either. Powers’ replacement, Ward Dotson who plays guitar, called the album disastrous. In an interview during the twilight of his career, Pierce was congratulated for delivering such a fine album, and proceeded to mercilessly deride the journalist’s compliment. So, is its inclusion here an act of folly or simply sheer contrariness? Not so. We’ve included it here for one very simple reason – more than any other of their albums, it has the highest concentration of brilliant Gun Club moments. Chris Stein’s anaemic production? Yeah, I hear you. Blah blah blah… You want the best post-punk collection of primitive American rock’n’roll songs? Look no further.

‘Carry Me Home’ and ‘Like Calling Up Thunder’ showcase Pierce’s shrill atonal wailing which almost drowns out Dotson’s atmospheric slide guitar, the latter track also featuring a brilliant rumbling Fall-like rockabilly rhythm. ‘Brother And Sister’ opens up promisingly (‘Sins of me, buzz and hiss in the trees/Their little skeletons will harm no one/Why do you bring them, always back to me/Their kingdom come and their will be done/On Heaven and earth and me’) but ends up feeling a little stiff and contrived. Thankfully it is followed quickly by a sizzling cover of Creedence’s ‘Run Through The Jungle’ – here Pierce multi-tasks with a strung out lead guitar, all the while sounding like he’s performing a frenzied shamanic ritual.

But the album hits ramming speed on ‘Devil In The Woods’ which along with Side Two’s ‘Bad Indian’ and ‘Sleeping In Blood City’ shares the thrilling two chord frenzy of ‘I Wanna Be Your Dog’ filtered through an exhilarating psychobilly spectrum. Bassist Rob Ritter alongside Dotson play with finger-shredding ferocity which even the flattened mix can’t disguise. Pierce’s delirious and savage delivery ensures these are three songs to make cacti bleed. Meanwhile the band give good range on ‘Texas Serenade’ where once again Pierce maniacal delivery is electrifying, this time strewn wildly over Mark Tomeo’s woozy steel pedal.

‘Watermelon Man’ is the bands very own ‘Walk On Gilded Splinters’, conjuring images of blood spattered Creole dolls – one can almost hear the bells jangling out their rhythm on Pierce’s wrists. If the band’s take on the standard ‘John Hardy’ is an archetype for the cowpunk of early Meat Puppets, nevertheless I somehow find myself singing along to Roxy Music’s ‘Editions of You’ – which despite its futuristic aspirations shares with it the same basic blues roots. Meantime, ‘The Fire Of Love’ out-Cramps Lux and Ivy with a big proud garage stomp. The closer ‘Mother Of Earth’ is almost a straightforward country rock track (once again enhanced by Tomeo’s steel pedal cameo), but masterfully evocative of the wide open desert spaces and consequently a fitting finale to an album which couldn’t have been made anywhere else in the world or by any other band in the world.

There was a time in the not too distant past, where UK independent record shops boasted bulging ‘Americana’ sections. I can’t imagine that record stores across the North Atlantic would have replicated this bumbling genre-lisation. That would surely be meaningless in the US, but I am honest enough to admit my ignorance in this regard. Nevertheless, I could partially identify with this (anxious? nostalgic?) millennial movement to recapture in a post-postmodern culture a sense of ‘authenticity’ or ‘rootsiness’. However, often the albums stacked up on those shelves were uninspiring rewrites of ‘After The Gold Rush’ ‘The Band’ ‘Grievous Angel’ and the like. If you want real Americana, why not hear the whole history of American rock’n’roll music in one band? Pierce’s travels took him to every corner of his homeland in his efforts to distil the mythical elements of that sound. From sleeping rough in New York to learning voodoo from Haitians in New Orleans, Pierce searched long and hard for the holy grail. His journey wasn’t a wasted one. I hear in the music of The Gun Club the wounded mutant blues of Charlie Patton, Bo Diddley and Howlin’ Wolf, traversing desert, prairie and swamp to revisit the voodoo incantations of Dr. John, freeloading along the way on rockabilly, exotic southern-fried trash and bad-ass LA punk, and simultaneously nailing the garage sound of ‘Psychotic Reaction’, while stretching out along the highway to envelop ghostly torch song and murder ballad. ‘Miami‘ tells its compelling version of the story of American rock’n’roll with the spikes and bristles flattened out in the mix, yes, but with the most indelibly bewitching treasury of songs imaginable. (JJ)

67. SPRING HILL FAIR – GO-BETWEENS (1984)

Gig-going regrets? We all have them- some can still be rectified, others can’t and some, owing to accidents of birth and geography, are too futile to dwell on but my realistic reasons for ruefulness include: never seeing Jeff Buckley or Stereolab; not seeing REM until 1989; being compelled to pass on an Al Green gig owing to farcical ticket prices and deciding to go and see the Cramps a second time.

But my most lingering pang arises from a calamity with the Go-Betweens in 1997. Having fallen hard for them after seing them a decade earlier and mourned their demise three years after that, their resumption was like discovering that a treasured item feared binned had actually been sitting in the cupboard all along. The cupboard on this particular Friday night was Glasgow’s Garage; at this time, I was working some 60 miles from the city and, as a rule, stayed away during the week then returned at weekends.

That evening, I got away from the office later than I’d hoped and arrived, flustered and frustrated, to hear them playing Draining The Pool For You, followed by Bachelor Kisses. Their set ended about 20 minutes later and the intakes of breath which followed my revelation of the first songs I heard told me just how much I’d missed.

The fact that this still rankles to the extent it does 18 years on speaks partly of a petty inability just to let go – but also of how much the Go-Betweens have come to mean to me. And those two songs can be found nestling on Spring Hill Fair, as fine an introduction to them as any of their albums.

Practically everything that’s been written about the Go-Betweens over the past quarter-century – including, I confess, a piece written by me as a callow student in 1990 – has laid great emphasis on the chasm between their critical acclaim and the quality of their music on one hand and their commercial success on the other. I see little value in going over this well-worn ground once again – what counts is that their music exists and is easily tracked down. Those who have yet to hear them are to be envied.

Spring Hill Fair, their third album, captures them in transition. Often, this can mean a patchy record with inconsistent focus – think of Another Side Of Bob Dylan, where there’s a Ballad in Plain D for every Chimes Of Freedom – but here, the subtle shift from the coiled-spring dramas they had so far specialised in to more elegantly crafted portraits is rounded and complete, meaning that the shift is no clunking handbrake turn but is seamless, almost imperceptible, bound together by the unifying theme of the turmoil of adult, but still often quite irrational, romantic intrigue.

Bachelor Kisses (introduced that fateful night at the Garage as “a song from France 1984” despite being the only Spring Hill Fair song not recorded there) opens proceedings and it’s a challenge to put into words how exquisitely beautiful it is. Clouded in a mist of synths so all-enveloping that they haven’t dated a second, it no more strays into sentimentality or smarm than William Blake strayed into limericks, tethered as it is by a rough-edged guitar solo which only casts the song’s sweetness into greater relief – as do the harmonies of the Raincoats’ Ana Da Silva (credited as Anna Silva) . Grant McLennan gives a warning to stay away from the cads and sugar daddies but does so without being patronising – it’s not a message to be given lightly (“Hands, hands like hooks/You’ll get hurt if you play with crooks”) and it can yield rewards (“Faithful’s not a bad word.”)

Five Words captures the Go-Betweens in-between, the looping melody straining and almost snapping but finally pulling itself straight against Lindy Morrison’s marching-yet-still-dragging its-heels beat. The words turn out to be “Bury them don’t keep ’em” – memories? Secrets? We never learn – another enigma from some of the finest purveyors of them. The ’80s produced few songs as restless yet simultaneously sure-footed as You’ve Never Lived, where a laser of a chorus cohabits with guitars that seethe like troublesome insects as Robert Forster delivers some of the finest of his many lines of suavely savage self-deprecation (“I’m no genius, just a former genius, a shadow of the genius/That I am.”) It’s the concoction that Franz Ferdinand have been grasping after for the past decade but have never quite clutched.

He’s at it again on the imperious Part Company, where there’s a brief mock-epic flourish (“From the first letter I got to this, her Bill of Rights”) and Forster’s brilliantly offhanded truncation of the middle syllable in “company,” as if to undercut the elegance that surrounds him, from the solemnly enunicated guitar figure to the ghostly apparel of that most ’80s of accessories, the Prophet synth, which is saved from being trapped in dayglo amber by its near-perfect mimicry of a theremin.

The McLennan monologue River Of Money has been compared more than once to the Velvet Underground’s The Gift but the similarity is more musical than lyrical, with a shared muscular, squealing feel to the backdrops. Where The Gift is a fully-realised short story, with plot, action, shifts of scene and grim twist, River Of Money is more meditative; it observes a general state of mind (“It is neither fair nor reasonable to expect sadness to confine itself to its causes”) and applies it to a particular case of him having to accept she’s gone and won’t be back. He fails, her memory blotted out neither by travel (“Snow which he had never seen before, was only frozen water”), drink (“Bottles had almost emptied themselves without effect”) or even simple domestic pleasures (“The television, a samaritan during other tribulations, had been repossessed). In this, it has more in common with Lou Reed’s solo Last Great American Whale – which appeared four and a half years later. An influence? We’ll probably never know but it’s an intriguing thought.

Forster’s now notorious theory, expounded in his book The 10 Rules of Rock and Roll, that an album’s penultimate song is always its weakest is comprehensively disproved on Spring Hill Fair. McLennan’s Unkind and Unwise is almost the archetypal Go-Betweens song, with a locomotive thrust and a semi-autobiographical lyric speckled with natural imagery (“Burn in a river tangled with reeds/While a crane on the water silently feeds”) and sneaking in at just under three minutes, it dabbles in perfection and decides to hang on to it. There’s some fun had on the lyric sheet of Spring Hill Fair, with droll asides dotted across the songs, and the fade of Unkind and Unwise is heralded with “(repeat till cicadas join in the fun).” Blow me if I didn’t have to reach for the dictionary and discover that the song would be fading long into the night with cricket-like creatures.

In his excellent biography of the Go-Betweens, David Nichols asserts that Spring Hill Fair “doesn’t quite seem to come up to scratch” and suggests it may be too diverse to be cohesive. To me, though, most of their albums are fully-formed, with the right balance of meticulousness and all-too-human humanity to ensure the right songs are chosen and put in the right place; it’s hard to imagine Spring Hill Fair in any other order or form. They also hold Forster and McLennan up as one of the great songwriting partnerships; in true Lennon-McCartney fashion, the co-credit often belies the dominant presence of one half (though Five Words has at least lyrical input from both) but the presence of the other half is always tangible.

It was their only album on Sire – a brief sojourn between Rough Trade and Beggar’s Banquet. Two months later, Sire issued Madonna’s Like A Virgin and there was no competing with that – but there I go into the forbidden territory. I’ll limit myself to observing some of the belated recognition that has come the Go-Betweens’ way, at least in Australia – the Go-Between Bridge in Brisbane, Cate Blanchett declaring herself a fan and Streets of Your Town (from 1988’s 16 Lovers’ Lane) finding its way on to an iPod’s worth of Australian music (which also featured 13 songs by pedestrian rocker Jimmie Barnes) given to Barack Obama in 2011 by Australia’s then Prime Minister Julia Gillard – and to regretting deeply that much of this came too late for McLennan, who died in 2006 at the shockingly premature age of 48.

I bought Spring Hill Fair in Bordeaux for 10 francs – roughly equivalent to £1 or, at the present rate of exchange, €1.42. A week earlier, I bought Robert Wyatt’s Rock Bottom (qv) in the same city for the same price. My spokesman, Pete Townshend, has prepared the following statement: “I call that a bargain – the best I ever had.” (PG).

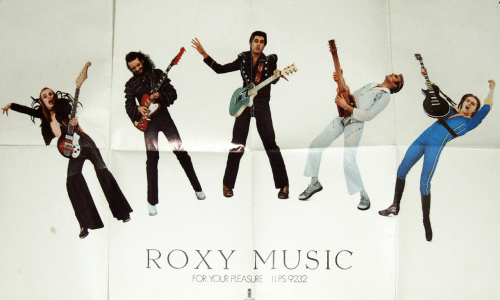

66. ROXY MUSIC- FOR YOUR PLEASURE (1973) Guest Contributor – Paul Haig (Josef K)

I remember seeing a billboard in Edinburgh for something called Roxy Music, it was 1972. The blown up image was a 1950s-style album cover featuring a stunning female model (photographer Karl Stoecker shot the cover with model Kari-Ann Mullerand) and I thought to myself, what is Roxy Music? It didn’t take me long to find out in the music press that it was the debut album by an English art school band who dressed in totally out-there glam gear and got shouted at when they played live for being somewhat effeminate looking. The first ‘Roxy’ music I heard was the single ‘Virginia Plain’ then I bought the album which was amazing in every way. Unfortunately, I was a bit too young to be going to rock concerts so the closest I ever got to seeing early Roxy Music was when I was on the top deck of a bus going up Lothian Road and saw them get out of a black limousine to walk into the foyer of the Caledonian Hotel in Edinburgh’s West End. They were wearing all their glam clothes and looked amazing so it was a real bummer to miss the concert which I think was at the Odeon cinema.

I first saw the sleeve for the second album ‘For Your Pleasure’ at Bruce’s record shop in Rose Street. Due to lack of pocket money funds I was unable to buy it for what seemed like an eternity so I would go in just to ogle it and try to imagine what tracks like ‘The Bogus Man’ would sound like. It looked dark and sinister and featured model Amanda Lear (who also started a career as a disco singer in the mid-seventies) in a contorted pose, wearing a skin tight leather evening dress and tottering awkwardly on high healed stilettos while leading a black jaguar on a thin leash. The background seemed like a futuristic Las Vegas city skyline and if you opened out the gatefold Bryan Ferry was on the left dressed as a chauffeur beside a black stretch limo, grinning ambiguously from ear to ear.

FYP has always been slightly overlooked as the progressive and cutting edge follow up to the eponymous first album that it was. Released only eight months after the slightly more tuneful eponymous debut it takes things even further in terms of sonic experimentation and artiness. Eno was still in the band at this point and his contribution to the overall atmosphere and ambience was crucial to the depth and texture achieved. He left due to tensions in the band after they toured the album in 1973 and things were never quite the same. Amongst the highlights are the sound effects on the title track and his crazed synthesizer solo, which is pure Sci-Fi jumping out of ‘Editions of You’.

You can just imagine his ostrich feathers being ruffled as he was playing it. Like most great records the opening track demands attention, ‘Do the Strand’ is a precise and accurate introduction and a perfect album opener. Stabbing staccato electric piano chords jump straight in along with the lead vocal:

“There´s a new sensation, a fabulous creation, a danceable solution, to teenage revolution”

which is reminiscent of ‘dance craze’ records from the sixties like ‘The Twist’ and ‘The Loco-Motion’ except ‘Strand’ appears more sinister, as if it could be the clinical answer to placate and quell the rise of the troublesome teenager. However, it’s probably nothing to do with a fictional dance craze we never learn the moves to and more likely an overall present moment coolness encompassing music, fashion, lifestyle and image. If you did the Strand, you were ‘in’ the ‘in crowd.’

There are only eight tracks on the album possibly due to side two featuring the nine minute and twenty second progressive, psychedelic tinged uneasy sounding and weirdly wonderful epic ‘The Bogus Man’ which features saxophonist and oboe player Andy Mackay playing incongruous and a-tonal parts which somehow work in the context of the song. It easily could be the soundtrack to a horror b-movie or a cry in the dark at Halloween. Towards the end you get Bryan Ferry’s heavy exhausted breathing with the faint sound of the backing music track bleeding from his headphones.

‘In Every Dream Home a Heartache’ was one of the songs we covered in TV Art which was the band before Josef K. I have a vague memory of performing it in a cellar bar in Edinburgh and instead of attempting to emulate the flanged psychedelic finale of the original we stopped it dead after the famous climatic line “But you blew my mind”. Probably a wise move. It’s an amazing lyric for the time, a sinister monologue that portrays the dissatisfaction and ennui of the narrator over his self-indulgent living and vast wealth.

Phil Manzanera is an integral part of the sound on early Roxy albums and shows off the uncanny ability to throw really catchy and commercial guitar riffs into most of the songs, as well as punky rhythms and memorable solos. His rhythm part on ‘Editions of You’ really drives the track. The guest bass guitar player is John Porter who became a successful record producer as well as working at the BBC for a couple of years. I actually ended up working with him when I was doing a session for the BBC in 1983, which he produced. One of the tracks,’ On This Night of Decision’ appeared on the B-side of the ‘Justice’ 12-inch single released on Island records. I wish I’d realised that he’d played on FYP at the time!

Eno is again very present in the title track and final song on the album, it is testament to how his synthesizer doodling and taped echo/delays could weird out and enhance a Roxy track, something that was sorely missing in future productions as the band became more commercially orientated from the third album onwards. It’s a haunting kind of stop/start track with precise tom tom fills throughout, one of drummer Paul Thompson’s best recorded performances with Roxy. A Duane Eddy style guitar part follows the vocal melody and warped taped echo/delay piano/keyboards. Mellotron strings and choir (also used on The Bogus Man) build slowly with distant tortured distorted guitar, endless drum rolls and cymbals tumbling around everywhere. I still like the part around two minutes in just before the long finale where everything is stripped away to leave Ferry’s dry a cappella vocal:

“Old man, through every step a change, you watch me walk away, Ta-ra”.

“Ta Ra” repeats over and over until it slowly fades into a cacophony of dark sound then distant monk like chants, before it closes with the voice of Judie Dench sampled by Eno from a poem quietly saying ” You don’t ask why” in the background. What does it all mean..eh? (Paul Haig)

Click the link below for our review of Josef K’s wonderful ‘Sorry For Laughing’, featured earlier in the series:

65. LAURA NYRO – NEW YORK TENDABERRY (1969)

Can a troubled artist create great art? Not according to Van Morrison, who once claimed that ‘you’ve got to be happy’ to produce your best work. But Van himself sounded like a man in pain when he made the majestic ‘Astral Weeks’, and there is certainly a counter argument to his assertion. Consider for example, Sly’s fractured and frazzled ‘There’s A Riot Goin’ On’, Dylan’s post-marital post mortem ‘Blood On The Tracks’, the austere desolation of Nick Drake’s ‘Pink Moon‘ or the neurotic but bleakly transcendent ‘Sister Lovers’ by Big Star – astonishing albums created under great psychological duress. You may wish to add to that impressive little list ‘New York Tendaberry’, Laura Nyro’s stark but affecting masterpiece from 1969.

Can a troubled artist create great art? Not according to Van Morrison, who once claimed that ‘you’ve got to be happy’ to produce your best work. But Van himself sounded like a man in pain when he made the majestic ‘Astral Weeks’, and there is certainly a counter argument to his assertion. Consider for example, Sly’s fractured and frazzled ‘There’s A Riot Goin’ On’, Dylan’s post-marital post mortem ‘Blood On The Tracks’, the austere desolation of Nick Drake’s ‘Pink Moon‘ or the neurotic but bleakly transcendent ‘Sister Lovers’ by Big Star – astonishing albums created under great psychological duress. You may wish to add to that impressive little list ‘New York Tendaberry’, Laura Nyro’s stark but affecting masterpiece from 1969.

Reviews of the album are characterised typically by comparisons with Joni Mitchell and Carole King, alongside a complaint that the arrangements are discomfortingly sparse and the music frustratingly out of character, the least joyous of her career. There is some uncertainty about Laura Nyro’s emotional well being at the time of the recording. The lyrics at times allude to a dark crushing sorrow, an unbearable distress, and the music has an unmistakable solemnity in places, as if she had shut herself away from the world and it’s troubles. And yet, one senses, even in the more introspective compositions, a brooding at times rapturous intensity, where the most intimate secrets are involuntarily unleashed in impassioned bursts which sound as euphoric as they are harrowing.

A more accurate musical touchstone than ‘Blue‘ or ‘Tapestry‘ would be something like ‘Laughingstock‘ by Talk Talk or ‘Climate Of Hunter’ by Scott Walker, perhaps even those John Coltrane albums of which she was so fond. There is an improvisational approach to the performances, a rudderlessness or – if you prefer – a wilful disregard for conventional song structure, which makes New York Tendaberry a comparable listening experience. Nyro was unable to write music. Instead, she “[held] the music in [her] head and [wrote] the lyrics down.” Her memory bank must have been bursting at the seams as she settled down to record some of these complex jazz and gospel inspired pieces for her third and finest album in early 1969.

Nyro empties those lungs, working her tonsils hoarse with abundant expressiveness, showcasing that extraordinary vocal range. Whether her voice caresses and purrs or lets rip piercing shrieks and wails, she is by turns little girl lost, now the bruised bastard daughter of Billie Holiday, or on occasion a frenzied howling banshee – sometimes all of these within a few short moments. The songs themselves frequently traverse several changes of mood and tempo. One (‘Tom Cat Goodbye‘) resurrects itself at least three times just as it’s embers appear to die out – it leaves me feeling exhausted, my head ransacked after Nyro’s dizzying energy-sapping performance.

On the album’s opening track, the exquisitely judged ‘You Don’t Love Me When I Cry‘, Nyro’s affliction (whether drug induced or man induced) yields the most naked of confessionals [‘I want, I want to die/You don’t love me when I cry/Made me love to play/Made me promise I would stay then you stayed away/Mister I got drawn blinds blues all over me’] The production is superb, crisp and understated, and Laura’s supple delivery incredibly heartrending.

Carving out similar territory are the haunting ‘Gibsom Street’ [‘Don’t go to Gibsom cross the river/The devil is hungry, the devil is sweet/If you are soft then you will shiver/Gibsom, Gibsom street/I wish my baby were forbidden/I wish that my world be struck by sleet‘] and the beautifully understated title track which provides a fitting finale to an album replete with references the devil, Lucifer and forbidden fruit – perhaps the reason it is often misconstrued as a thinly veiled narrative documenting a personal narcotic meltdown.

Throughout, the arrangements are superb. While the more upbeat tracks, such as ‘Mercy On Broadway’ retain the buoyancy of some of her ‘First Songs’, the gunshot and gospel break is inspired – infinitely more subtle and imaginative than the more explicitly commercial production of the first two albums. Both ‘Sweet Lovin’ Baby’ and the album’s most celebrated track, ‘Save The Country’ while more readily identifiable as ‘classic Laura Nyro’ bristle with a passion and inventiveness missing from those earlier outings. It is here on ‘New York Tendaberry’, where she presents the fullest exposition of her remarkable artistry.

I first read about Laura Nyro in a Melody Maker series from around 1987 entitled ‘Pop! – The Glory Years’, which turned me on to Tom Rapp and Syd Barrett amongst others. The article on Laura Nyro spoke of a woman who had wrestled with demons, perhaps the devil himself, and one sensed she had come out second-best in the tussle. Implicit in this account – which focused primarily on New York Tendaberry – was Laura’s supposed battle with heroin addiction, subsequently disputed by many. When I finally found an old second-hand copy, it quickly wormed its way into my consciousness. Whatever the truth regarding Laura’s drug use, it was plainly clear that here was someone laying her soul bare for all to hear. I remember exactly where the vinyl crackled in those spaces between the deftly nuanced orchestral and brass arrangements. It is in those very gaps that the album utters it’s unique language and it feels odd to listen now to those silent passages on CD, neutralised by their digital subjugation. Laura herself saw it as her most natural, even visceral recording. “It is not an obvious one…not one that you really even listen to, because it really goes past your ears and it’s very sensory and it’s all feel…it goes inside, like at the back of your neck, or something. It’s abstract, it’s unobvious and yet I feel that it’s very true. I feel that it’s life, what life is to me anyway.” Laura’s own life would of course end tragically prematurely at the young age of 49. Her legacy however is secure – a series of superb albums (all wheat, no chaff), of which this is her greatest accomplishment. (JJ)

64. T. REX – RIDE A WHITE SWAN (1972) Guest Contributor – Johny Brown (Band of Holy Joy)

Proper albums would follow: Aladdin Sane, Psychomodo, For Your Pleasure, The Slider etc. This was the first record though. The first long playing record that I had bought on my own terms, using my own money to furnish my own, budding, and quite contrary, taste. Ride A White Swan, on the dreaded and much derided Music For Pleasure label. It cost 72 of the new pence and was bought from a Woolworth’s in Nottingham whilst on a family holiday. I was 11 years of age. It was 1972.

Proper albums would follow: Aladdin Sane, Psychomodo, For Your Pleasure, The Slider etc. This was the first record though. The first long playing record that I had bought on my own terms, using my own money to furnish my own, budding, and quite contrary, taste. Ride A White Swan, on the dreaded and much derided Music For Pleasure label. It cost 72 of the new pence and was bought from a Woolworth’s in Nottingham whilst on a family holiday. I was 11 years of age. It was 1972.

It wasn’t remotely proper in the proper sense of what a proper album constituted, it’s impropriety stemming from the fact of it being a tacky cash-in compilation of old material between the cool label Fly and general industry chancer MFP to cash in on Marc Bolan’s newly found superstar success. No matter, I was instantly smitten by the maven weave of magic and dream that flowed out of the grooves.

I loved this first record to death, lost it and found it and then lost it again, and I had quite forgotten about it I must say, until a week or so ago when doing a Marsha Hunt inspired you-tube surf I was confronted by an image of the lurid and hyped Ride A White Swan cover.

It was a bit of a shock to say the least, and I clicked on the link with a bit of trepidation, wondering how it would sound after all these years. No worries though. It was the same raw beautiful sound of youthful memory that bellowed out. Better in fact: it lit up a drab autumnal week and put some proper fire into the leaves falling onto the pavements outside. I posted an Instagram of the cover on Facebook and quite a few other bods said the same thing – it was their first record and much loved after all these years. Way to go MFP!

Things got better still when Ant Cook of the quite superb Church of Elvis emailed to say he had a spare vinyl copy and would trade. Within two days I had the record in my possession and I’ve played it every free moment since. I’m not even going to try to be objective here. In fact, indulge me please as I head into the direction of gush overdrive. I just have out and out love for this record, and for the fourth or fifth time in my life, it’s hit me like a new infatuation. Here are a few thoughts…

Let’s start with that sleeve. The fabulous purple cover with ultra pink pumped lettering promises a kind of tacky magic. It says T.REX on the sleeve; this is of course a bit of a misnomer, as most songs here should be credited to the earlier Tyrannosaurus Rex incarnation. Made no difference to me at the time and indeed only served as a portal to discovering Bolan’s earlier work. I’m not going to quibble now either: the sleeve still looks magnificent and trashy and casts a weird spell upon the room. How about the music, the sound, the songs, the word, the voice?

The album itself begins with two absolutely monumental pop big hitters in Ride A White Swan and Deborah. This is Bolan at his seductive best, harnessing rock and pop and great surreal poetic couplets to ride out a flight of mad fancy. It’s a ride of cosmic insanity that carries you along all the way as Marc exhorts us to ‘wear a tall hat like a Druid in the old days, say a few spells and baby there you go’ Both songs still sound strong today and serve to put a spring in the step and a cheeky notion in mind.

Two reverb drenched mythical ballads Child Star and Cat Black follow. Child Star seems to be about some kind of Tibetan Wunderkid waiting in exile to return to his country. I’m probably wrong on the Tibetan Wunderkid front. Bolan sets out such a fantastic terrain it’s easy to populate it with mythical beings of your own imagination.

Cat Black is simply beautiful, it employs a classic rock and roll / doo wop chord structure to sing a hymn of lovelorneliness to a supremely distant hippy chick who I’d guess might be Marsha Hunt. I’m probably wrong again, but I don’t think that matters at all with these songs, they are all wide open to interpretation. Maybe bringing Marsha Hunt to mind is just an excuse to recommend you go on You Tube and search out her sublime cover of Walk on Gilded Splinters, or indeed her take on Stacey Grove.

Conesuela is next, followed by Strange Orchestra, and such a strange orchestra it is too. I have never thought of these songs as overtly psychedelic or psyche despite their cosmic allusions and punk drive, rather it’s kind of a weird ecstatic pop the act forges, never quite druggy but always mystic with one eye firmly on the important teenage things of the day like fast women, smart cars and streamlined clothes. Bolan’s singing often seems both rushed and slurred with a kind of drugged excitement though, and I like that. I like that I can’t always understand the words: again, it allows my own interpretations to flourish. Peregrine Took’s percussion is frantic and intense and propels the sound on in great skittering surges. Mickey Finn was a bit more laid back in the later incarnation. All of them beyond good looking: style-saturated Ladbroke Grove cats, which adds extra pop dust to the starry mix.

Lofty Skies is one of the greatest songs ever, a visionary heroic love song that always inspired a kind of Northern Mysticism on cold winter mornings when I was 19, looking for another world through Magic Mushrooms and Liebfraumilch, and then later in London, in the early hours of coming down off a speed fuelled night, the song always pointed to some other wilful and more Wyrd world beyond this stupid one. I was always prone to a bit of astral flight and imbued with cosmic yearning. Never quite managed the corkscrew hair mind…

Mucho silliness yes, Narnia Glam Racket indeed and pure wilful cosmic escapism without a shadow of a doubt and, all the better for it. Lofty Skies is blessed with one of the greatest wah wah guitar solos ever and I’m happy to report that all these decades later it stands. The whole record in fact sounds better to me now than it did then, makes more sense, fires the spirits, sends new shivers, in a purely different older way of course. The crushed velvet has faded but the fist heart mighty dawn dart remains strong and true and hey…

King Of The Rumbling Spires is magnificent and tribal, tremulously so, with a chorus that makes you feel ten foot tall and ready to be like the true ruler of Narnia, or the outside bet in Game of Thrones and yeah, this monster song, really takes off when the mellotron kicks in. The album ends with the deranged rural boogie of Elemental Child with dance, dancers a dancing as a truly rocking Bolan lays bare the torch girl of the marshes. The songs as a whole have me bopping around the room and Bolan’s voice transports me and even now as a grown man I swoon to a croon that is rare velvet, and as precious and as fragile. Gorgeous!

What I love most about this album listening to it now, are all the clicks and trills and whoops and bangs that flicker through Tony Visconti’s production. These sounds are probably not things that I would have picked up on at the time. The sonic blast has enlightened some blank days of late and transported me to other spaces awhile. He lords it over this record in a manner similar to the way Martin Hannet did with Unknown Pleasures. His use of strings, effects and organs turns every song into a mini pop odyssey. Fuck it, it’s 7 30am and I’m going to play it again, right now, loud.

I lost track of my copy after leaving home but weirdly enough came across it again around 1990 when Band Of Holy Joy played the legendary Surfers club in Tynemouth and I took a pre gig browse in a car boot sale, and found it, with my name written on the insert, and along the balloon typography, much like ‘Andy’s’ on the You Tube post.

The cost that time was 50p and 20p admission fee, so 2p cheaper than the first time around. With all the moving about I’ve done in London I soon lost it again mind and along with my lost copy of Prince Far I’s Under Heavy Manners, the early Pistols and Banshees and some Bowie bootlegs, it was always the slab of cardboard and vinyl I wish I still owned. All of them have the same depth of wonder and perpetrate similar crude sonic magic. Which is always what I look for and want in any piece of music. This time around it cost me a copy of Land Of Holy Joy and I’m determined to hold on to it for a few more years yet. I know one thing, it’s came into my life again at a good time. It is a record that has magic in spades, and stars in buckets, a shiny truth in every glam grain of sand, it’s an exotic treasure of the popular past washed up on the drab shoreline of my present, and for that I’m grateful. Major thanks to both Ant Cook and Marsha Hunt for bringing it back into my life. (Johny Brown)

Click here for our review of The Band Of Holy Joy’s brilliant debut ‘More Tales From The City’:

63. BO DIDDLEY – BO DIDDLEY (1958) Guest Contributor Tim Sommer (Hugo Largo / NY Observer)

Rock’n’roll is the only good thing to come from the American stain of slavery and the institutionalized race hatred of Jim Crow. The connection between race and rock is often alluded to, but rarely discussed in anything but the most superficial detail. I suspect people would rather not be confronted by this fact: those who were the most battered, discarded, and discredited by the American dream invented the music that defines our lives. Eric Clapton talking about Buddy Guy or Robert Plant mumbling a few words about Clarksdale doesn’t teach us a goddamn thing about that. Their lip service to some airbrushed sepia-toned blues ideal is a smiley face painted over the fact that people were kidnapped from their continent, jammed into slave ships where they wallowed in their own shit and vomit for months, and then they and their descendants were committed into chains and forced servitude; the rhythms, rhymes, and melodic traces of those people lay the groundwork for our music.

The entire foundation of Pre-Beatles rock was built by those shut out financially and politically from the American dream, consigned to menial jobs in an inescapable American underclass caused by Jim Crow and insurmountable barriers in class and education. Likewise, it’s important to understand that although the Beatles have come to personify a certain aspect of the 1960s’ cultural rebellion, this had virtually nothing to do with the challenges to authority posed by rock music in the 1950s. Rock in the 1950s – and that includes white appropriations, like Elvis or Jerry Lee Lewis – threatened people because it carried the aroma of the disenfranchised classes, particularly African Americans. The Beatles, on the other hand, just empowered middle class and upper class white people to wear their hair long and dress funny. This kind of stylistic rebellion is far, far less threatening than the potential class and cultural destabilization posed by music that was directly descended from the semi-permanent American underclass made up of former slaves (rural and urban) and poor rural whites.

Now, sometimes, explaining certain aspects of rock’s social and musical evolution can be done in a pretty simple manner. Do you want to understand the deep, almost Bronze-age roots of Rock’n’roll? Do you want to hear how the amazing, humming, thumping, and eternal groans, shouts, and hallelujah-songs of the deep and often horrific past resonate on your Mac Pro, today? Do you want to “get” how even though America gave it’s unwilling immigrants a gruesome eight-million ton shit bag of slavery to carry around, they still gave us back one of the most powerful and ubiquitous elements of our culture, Rock’n’roll?

Listen to “Bo Diddley,” the debut 45 by the singer of the same name, released in the spring of 1955. It pretty much tells the whole story, in two and a half minutes. Then go on and listen to his entire first album, released in 1958 and comprised of most of his single releases up to that point.

The melodic, lyrical, rhythmic and cultural framework of “Bo Diddley” had existed long before it was recorded in March 1955. That one song carried a millennia worth of anthropological baggage, yet it simultaneously invented rock’n’roll’s future.

The condensed version: American and Haitian Slaves of West African descent would do something called the “Juba” dance; it’s roots lay in the miraculous meters of their ancestral lands, modified and corrupted by some of the European reels, jigs, and clog dancing slaves in the New World were exposed to. Now, since slaves were banned from owning most drums or drum-type instruments (there was a fear they would be used to communicate with their brethren on other plantations), they learned to accompany their songs by elaborate clapping, slapping, and drumming on their own body. These two traditions – the Juba dance and the claps, chants, and slaps that accompanied it – came to be known as Hamboning.

By the late 19th Century, the couplets and rhymes that accompanied Hamboning had been fairly rigidly encoded; it was also being performed in Northern cities where the descendants of slaves had moved to seek opportunity and it had also spread to the rural white poor. Recordings or transcriptions of these archival Hambones are instantly recognizable as largely identical, both in meter and lyrics, to the song “Bo Diddley.”

In 1950, Alan Lomax, that legendary archivist of folk traditions throughout the world, sat in a classroom New York City’s Harlem and interviewed a 10-year old boy named Steve Wright. Under the watchful eye of a teacher, and with reverb-less close walls of the classroom clearly evident, Wright sang a song virtually identical to “Bo Diddley.” Likewise, in late 1951, popular country and western stylist Tennessee Ernie Ford (dueting with the considerably less famous Bucky Tibbes) released a single called “Hambone.” Melodically and lyrically, much of the song is identical to “Bo Diddley” (even it flattens out the hopping Juba rhythm into a fairly manic two-step).

Taken at face value, Bo Diddley’s fairly loyal interpretation of the ancient Hambone shouldn’t have made much noise. But there is far, far more to this story.

Not only does Bo inflate the Hambone with atomic gas, literally inventing the future of the rock electric guitar, he also repudiates the prohibition enforced on his ancestors and spells out the rhythm with real drums, primal and thumping with the power of ancient ceremony. “Bo Diddley” goes on to firmly encode the Hambone rhythm once and forever by both simplifying and elaborating it into the “shave and a haircut, 5 cents!’ format that will, from that moment forward, be known as The Bo Diddley Beat. Bo Diddley, on “Bo Diddley” (and many of the early 45s compiled on his first formal album), electrifies the trials, tribulations, celebrations, rhythms and voodoo of Disenfranchised America. He takes this story, a thousand years or more in the making, and adds a gorgeously profane noise that bridges the unimaginable past and the inconceivable future, swallowing the DNA of West Africa and spitting out the Sex Pistols.

“Bo Diddley” (not to mention “Hey Bo Diddley,” “Hush Your Mouth,” “Pretty Thing,” and “Who Do You Love,” all on that first album and all carved from the same ancient, profane, future-seeing, and holy magick) has the feel of some deeply strange folk music; yet winding around under, above, and alongside these ancient and venerable melodies are the guitar, that vastly important guitar. 50 years later, that guitar is still startling, a roaring and continuous wave of humming noise that can’t decide whether it’s going to summon the saints, the haints, or both. On a lot of these first-album tracks, Bo does nothing less than invent the modern rhythm guitar, laying the foundation for everything from the Kinks to the Velvet Underground to Black Sabbath and far, far beyond. Prior to “Bo Diddley,” the electric guitar had tic-tic-tic’d in a clipped rockabilly and hillbilly rhythm, or it had replicated the shortnin’ bread walking bass and sax lines of older jump blues, jazz, and r’n’b recordings. But for the first time, on “Bo Diddley” it just roars, it just goes whaggga whagga without stopping for breath, it just sounds like a plane whirring and a train picking up speed, all at the same time.

In fact, alongside Willie Kizart’s use of distorted electric guitar to play the walking boogie bass line on “Rocket 88” in 1951, what Bo does on “Bo Diddley” in 1955 is the most important development in the artistic evolution of the electric guitar. Bo just washes the rhythm, with no needling finesse, only a desire to create a butter-churned wall of H-Bomb electricity that somehow both emphasizes the ancient spirit of The Beat, while making it something totally new. After “Bo Diddley” the guitar would never be the same; this is Zero Hour at electric rhythm guitar trinity, the magic upon which our Ramonic future would be built.

There’s more, much more to Bo’s first, eponymous album; I mean, for god’s sakes, in addition to the flat-out fatback greasy-Delta-moonshot classics listed above, there’s theslurring, stomping “Diddy Wah Diddy” and the debut of the drunkass standard “I’m A Man.” Throughout, The songs are staggeringly simple yet complete, like passionate shorthanded notes to your voodoo sweetheart; and the album is so full of energy, joy, spontaneity, and a late-night blue-lit spirit that somehow the imperfections fit right in (“Before You Accuse Me” is especially marked by tuning inconsistencies and a few missed chords).

Prior to this, other singers had shrieked with lust and howled with hope and Hadacol; but no one had done it accompanied by the thrashing, throbbing, electrified spirit that humps and sizzles and drools through this album. This makes Bo Diddley the first modern Rock’n’roll record. You are hearing the old gods of Africa going though the Stargate built by Bo into rock’s future, where they still thrive.

Everything bright and brilliant and chunky and charging and simple and simply perfect about Rock’n’roll is contained in Bo Diddley. It is the moment where the future is invented, and the past opens its’ deprived, insulted, trashed but triumphant arms to welcome it. (Tim Sommer)

Click here for our review of Hugo Largo’s ‘Mettle’, the first ever post in TNPC:

62. HOWLING BELLS – HOWLING BELLS (2006)

HOWLING BELLS – HOWLING BELLS (2006)

It’s been widely accepted for some time now that “indie” has become a completely meaningless term, yet still the notion and concept persist.

Leaving aside the factual definition of a small record company’s business model and distribution method, the idea of indie-as-genre first evolved from Stiff, Factory, Step Forward and unnumbered others taking the practical step of recording, financing and distributing their own music to maintain it on their own terms and to pre-empt likely, though by no means inevitable, rejection by the majors of sounds that were in the main untutored and untroubled by anxiety over chart placings or courting the approval of a music establishment that was even sleazier and more putrid than had been apparent at the time.

At this point, the sound of indie labels was a loose, labyrynthine but endlessly rewarding aggregation of punk, electronics, R & B (another term to have since mutated beyond recognition), funk and myriad other items tipped into the soup.

Sometime around 1985, the definition was put on a far tighter rein – mirroring the retreat of the best mainstream pop from loose-limbed adventurism to lumpen, profit-chasing garishness – and indie came to mean guitar-based music in thrall to either the Byrds and post-Cale Velvet Underground on one hand or Captain Beefheart on the other. The former definition became preeminent and solidified at the end of the decade with the precipitous rise of the preposterously overrated Stone Roses, a good band – nothing more, nothing less – completely unequal to the ludicrous hosannas made on their behalf.

With the arrival of those who haplessly aped the even more overestimated Oasis, what had previously set this music apart from the mainstream – adventure, openness, empathy, quest – had been whittled down to a proscribed set of approved sounds and postures which resulted in utterly unremarkable music and which came to be known by the 21st century as landfill indie, though I crave the indulgence of offering my own coinage – I called it Gumby indie, as its oafish grunting unavoidably reminded me of the same in the Monty Python creations.

By the middle of the millennium’ first decade, Arctic Monkeys were perceived as the stationery-shovers but while they were several cuts above the sludge, owing in no small part to Alex Turner’s lyrical dexterity, they still weren’t quite what was needed. Around the same time, the saviours indie didn’t know it had quietly appeared – from Sydney, Howling Bells.

It’s difficult to pinpoint why they grabbed hold of the essence of this music when so many others hadn’t even come close. It’s an indefinable quality- there may once have been a time when I’d have felt able to call it the X factor without blanching – but it involves things like style, panache, a sense of dynamics and, quite simply, a strong feel for songwriting and melody. The absence of these things isn’t necessarily a problem in itself – some of the greatest music ever made has had little tune to speak of – but if you’re just going to make a noise, you’d better have some substance to it and the sheer gormlessness of so much of what was peddled meant it held so few surprises and made so few demands on the listener that it barely seemed to exist.

And so Howling Bells and their dense, layered sound – which supports the songs rather than hanging around on its own – slotted briefly but perfectly into the formidable roster of Simon Raymonde’s Bella Union for their first album. The cover art reflects what lies inside – an illustration of an owl in a tree being pursued, with nefarious intent, from a ladder; it’s such an authentic French-and-American-revolution period pastiche that I was surprised to discover it was actually commissioned for the album and, similarly, Howling Bells grapple so skilfully with their largely ’80s/early ’90s influences that it seems of a piece with them, while still being unmistakably 21st century.

Take opener The Bell Hit, which has an almost stage musical feel, a doleful intro (curiously reminiscent of Mary Hopkin’s Those Were The Days – or, if you prefer, Dorogoi Dlinnoyu, the Russian folk song it’s based on) giving way to a jazzy sashay which could support an unwelcome singalong in the wrong circumstances but, left to its own devices, casts a sunburst into the sorrowfil refrain “Promises are empty in a world of empty bliss.”

There’s palpable contrast in Low Happening – the first of the album’s four singles- where two of the more obvious Howling forebears, Pixies and PJ Harvey, swerve around each other in brilliant discord on the album’s most blatantly abrasive moment. It’s run close, though, by Blessed Night, where Juanita Stein sets out what resembles an abridged version of the non-credo of John Lennon’s God but still grasps for something, or someone, to take her belief to (“Don’t believe in the stories I hear/Don’t believe in the things you fear/Give me strength/Give me time/Give me you, now”) against a simple but inescapable Spanish/Moorish guitar figure from her brother, Joel, and Glenn Moule’s drum pattern spelling out a dire warning.

The nocturnal theme recurs on The Night Is Young, where Juanita darts in a breath from desolate (“When I needed you to stay/Drove your car the other way”) to defiant – with a nifty mixed metaphor for good measure (“Oh,me – don’t you worry about me/Got a pocket full of wisdom up my sleeve) in one of the most expressive and affecting voices of recent times. She doesn’t quite sound Australian but neither does she sound Pom and definitely not faux-American; she sings in a human accent, with no need for subtitles.

Setting Sun, the first toll of the Bells I ever heard, is the most markedly commercial song here but still retains oddness in a rhythm that piledrives even as it’s hushed, a solo from Joel which as uncomplicated as the one on Buzzcocks’ Boredom yet still yields up subtletly, and Juanita capturing the frustration of running out of time while being resigned to it happening: “One more day’s not enough to change the world/But we’ll rise and fall beside the setting sun.” There’s probably a mathematical formula that can unravel why this wasn’t a hit; maybe there’s a generous prize on offer for another formula to make it the hit it’s not too late for it to be.

Four albums in now, that hit continues to elude Howling Bells but the definition of what makes a hit is narrower and more predictable than it’s ever been. The web-driven collapse of the conventional music industry should have cleared the way for uninhibited adventure but conservatism still holds sway. Howling Bells may not be avant-garde but they’re vastly inventive and stand as a reminder of what’s still possible, as well as the solar system of difference in music between being ambitious and having ambition. Howling Bells, like much indie worthy of the name – and like the best of any genre – are ambitious; Gumby indie merely has ambition, for sales, for ever-vaster venues, for heavy rotation – for tedium. Hear Howling Bells – hear the difference (PG).