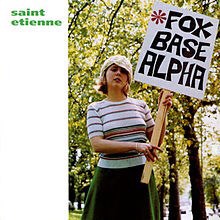

FOXBASE ALPHA – SAINT ETIENNE (1991)

FOXBASE ALPHA – SAINT ETIENNE (1991)

‘Record collection rock’ was a phrase tossed around with vigour and no little relish in the early ’90s. It epitomised a mood of intense self-consciousness and an eagerness to have and eat cake – to demand that music be dumb, artless, rock ‘n’ roll (adjective more than noun) yet still be dissected within an inch of its life.

It was a loaded phrase, at best mildly cynical, at worst plainly pejorative, telling as it did of a genre perceived to have nowhere left to go but to recondition its past and reassemble prepackaged ingredients. But hadn’t this already been going on for decades? Wasn’t half the Beatles’ early repertoire drawn from the rock ‘n’ roll, r & b and soul records they eagerly acquired after they passed from the US Navy into eager young Merseyside hands? Wasn’t the mythical meeting of Jagger and Richards at Dartford railway station occasioned by the clutch of blues albums the former was holding, just some of the many the Stones would go on to plunder for material? And while it’s debatable how many records he may have been able to afford to buy, was Elvis not a human jukebox, absorbing everything he heard – and covering much of it, often radically- on the radio and at the diner?

The truth is, record collection rock is as old as rock itself and even Simon Reynolds, one of the writers most exercised by the concept, was compelled to concede around the end of 1991 that three of the albums which had given him most pleasure that year were prime examples of the art: Primal Scream’s Screamadelica; Teenage Fanclub’s Bandwagonesque – and Saint Etienne’s Foxbase Alpha.

Maker writer Bob Stanley found himself embroiled in this debate, not only through what he wrote but also by being written about by his colleagues as he pursued extracurricular adventures in the Saint Etienne ranks. In his tastes, he was an entire mischief of magpies on his own, devouring acid house, French yeye and bubblegum with equal relish, while also finding a place for the perceived higher art of canonical acts. He was rightly withering of many of his contemporaries, bewildered by “people who got into music two years ago who think Jesus Jones are better than the Beatles” and saw no cause for celebration in the supposedly alternative mediocrities invading the charts in a charge of the featherweight brigade. Certainly, it was a grim time in a highly peculiar decade, in which many of the most prominent players gained their status from origins which were unlikely (Nirvana, Oasis, Primal Scream) unpromising (Radiohead, Blur, the Prodigy, Beck) or both (Manic Street Preachers).

All this, though, led to his needlessly absolutist claim that that pop music “shouldn’t be intelligent; it should be completely unintelligent.” I previously covered what I make of this view in my review of Blue Aeroplanes’ Swagger (no 35) but suffice to say I don’t agree; neither did one of Stanley’s colleagues, Andrew Mueller, who said it best when he chided his fellow Maker man with the unarguable caution: “Without intelligence, there is no imagination…the alternative doesn’t bear contemplating” and added that the quality of Saint Etienne’s music was “no mandate to talk such cobblers.”

The evidence of that quality runs through Foxbase Alpha like the Thames through London, the only city on Earth where it could have been made, one they paintly as richly as, if less literally than, the Kinks, Ian Dury and Madness. Despite this unmistakably metropolitan hue, though, Saint Etienne presented their hometown as much as a global crossroads as a mighty collision of villages, particularly much later in Tales From Turnpike House. The tour of their cosmopolis begins with a reminder of their Francophone roots, a snatch of radio dialogue introducing commentary on the football team who gave them their name and whose lurid green shirts were the last word in calcio chic in the mid ’70s.

Then it’s off to Laurel Canyon via Pimlico and Toronto for the song they announced themselves with – a cover of Neil Young’s Only Love Can Break Your Heart. About time we had some more heresy here at TNPC so here goes – I actually prefer their version to the original, which is, of course, a beautiful and poignant piece of work but it plays into the hands of Young’s detractors by sounding the way many of them think he always does. With the slightest tweak of the melody and the empathic tones of one-off guest Moira Lambert, Saint Etienne lift the song out of the maudlin and into the sweetly sorrowful by way of the dancefloor.

That’s one of their natural habitats and they stay there, in varying guises and modes, for much of Foxbase Alpha. Stoned To Say The Least kicks off with a wry sample from Countdown, the first programme broadcast on Channel 4 in 1982 and a staple there to this day. It’s fairly fitting, as it’s a close relative of the majestic The Sun Rising by the Beloved, whose singer, Jon Marsh, was a contestant on that very programme when his band owed more to the New Order of Ceremony than of Subculture. The subdued bass and swooping backwards guitar, congas and interjections of cowbell and Italian house piano all make for a compendium of the ideal early ’90s dance tune – but it still finds room to wrongfoot you with an extended feedback fade. Record collection dance music in action – and ignore anyone who tells you that sounds no fun at all.

The rapidly cliched perception of Saint Etienne was of Stanley, Pete Wiggs and Sarah Cracknell as a parallel universe Blue Peter team or red Routemaster bus travellers tagging along with Rita Tushingham and Adrienne Posta. They were always a good deal more nuanced and savvy than that but on London Belongs To Me, they provide the soundtrack all those films could have had if they’d just had a word with Delia Derbyshire. It strolls, cascades, shimmers like the sun that makes you realise you’ve forgotten your shades – on the summer day you have to remind yourself to savour every minute of. It shares only a title with the 1948 drama starring a young Richard Attenborough, already specialising in misfits, tearaways and purveyors of cold evil at outrageous odds with his latterday ‘Dickie’ persona.

Like The Swallow is as odd, ambitious and outright headswimming as anything a chart act – for that’s what Saint Etienne were – has ever come up with. The washes of sound it opens with resemble Mercury Rev’s Holes, Talk Talk’s The Rainbow, even parts of the very un-pop It’ll End In Tears by This Mortal Coil, and it proceeds, as steadfast and unhurried as a symphony’s first movement for three-and-a-half minutes before vocals are even considered and even then, it’s a Cracknell cameo – she’s gone in less than a minute, buoyed by percussion which in other places would sound martial but here prove that it is entirely possible – in fact, desirable – to march for joy. Speaking of drums, listen out for the snare thunderclaps that pursue a sampled Levi Stubbs through She’s The One – the sound of the Four Tops was once magnificently likened to the roar of a wounded lion and that holds true here as well, except this one has see Androcles run by with no time to pull out the thorn.

And do not dismiss Dilworth’s Theme purely because it’s the last song and is less than a minute long. In the spirit of the Time Bandits scene where Ian Holm as Napoleon rants about similarly petit conquerors (“Alexander the Great – five feet exactly…Tamburlaine the Great – four foot nine and three quarters) I give you a similar roll call of chronologically challenged but magnificent songs: Cockney Rebel’s Chameleon – 47 seconds; the Incredible String Band’s Son of Noah’s Brother – 16 seconds. Dilworth’s Theme – a dumpy little 38 seconds but

a beautiful, rainy day drawing room reverie, like Bowie’s Eight Line Poem with the comedy cowboy locked out of the house. The very fact that it’ll take you less time to listen to it than to read what I’ve written here about it says plenty about its condensed glories.

There’s more, much more, to say about this record but I’d need as many words to do it justice as there are in Peter Ackroyd’s London:The Biography – in a very odd way, a companion piece – or Bob Stanley’s own, staggering Yeah! Yeah! Yeah, which takes on the fearsome labour of charting the history of post-war popular music and triumphs, omitting nothing and vividly illuminating everything. Not unlike Foxbase Alpha, really (PG).