GIDEON GAYE (1994)

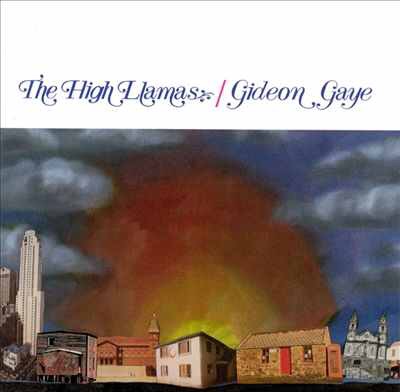

To begin at the beginning…Gideon Gaye is a record which creates a self-contained world, a place unto itself with its own cohesion, internal logic and quite possibly laws as well. It’s the kind of record which redeems the tainted notion of the concept album and shows that they don’t have to recount the stereotypical adventures of the intrepid warrior as he sets out to retrieve the golden artichoke from the five-headed basilisk. They don’t even need to tell a story at all, just have a thematic integrity and unity and, amid its recurring musical motifs, there’s a sense on Gideon Gaye of shifting scenes around a community (possibly the one on the cover, where a Gilliam-like collage depicts cottage, cathedral and skyscraper improbably nuzzling up to each other under glowering De Chirico skies), of delving into lives for a snapshot and all this makes Gideon Gaye nothing as fatuous as a rock opera ( something which began and ended with Tommy) but as close as popular music has ever come to its own Under Milk Wood.

To begin at the beginning…Gideon Gaye is a record which creates a self-contained world, a place unto itself with its own cohesion, internal logic and quite possibly laws as well. It’s the kind of record which redeems the tainted notion of the concept album and shows that they don’t have to recount the stereotypical adventures of the intrepid warrior as he sets out to retrieve the golden artichoke from the five-headed basilisk. They don’t even need to tell a story at all, just have a thematic integrity and unity and, amid its recurring musical motifs, there’s a sense on Gideon Gaye of shifting scenes around a community (possibly the one on the cover, where a Gilliam-like collage depicts cottage, cathedral and skyscraper improbably nuzzling up to each other under glowering De Chirico skies), of delving into lives for a snapshot and all this makes Gideon Gaye nothing as fatuous as a rock opera ( something which began and ended with Tommy) but as close as popular music has ever come to its own Under Milk Wood.

Highest Llama Sean O’Hagan has told TNPC, though, that it wasn’t conceived as a fully-formed suite or song cycle but that “it was obvious a musical theme was emerging” as the record took shape. Following the regrettable but perhaps inevitable demise of Microdisney (for further detail, see review 37 – Against Nature by Fatima Mansions, led by O’Hagan’s Microdisney partner Cathal Coughlan), O’Hagan delivered two engrossing if slightly tentative albums which embellished on the Microdisney template of finely etched, compulsively melodic songs, something he tells us culminated in “stifling professionalism-” always an occupational hazard when a major record company is clamouring for a hit.

A far smaller outlet, Brighton-based Target, would have had no such high-do demands and, under far broader influence than he was often given credit for (Albert Ayler, Fred Neil, Cluster) he declares he was ready for a change and “done with the Byrds and guitars.” Many observers, though, didn’t see beyond the layers of harmonies and the tidal melodies, and the obvious – in fact, somewhat lazy – Beach Boys comparisons must have left O’Hagan feeling like a comedian repeatedly entreated to reprise his catchphrase. Speaking of guitars, this was like the common experience of, say, Big Star or Orange Juice receiving the verdict “sounds like U2/Oasis/Coldplay” for no better reason than their preponderance of guitars.

Some were content to infer that the title of The Dutchman was a nod to the Holland album by all those Wilsons but how often did they have such swooning, swooping strings? Would they ever have sung about “streets that were laid with distress”? In fact, I detect several traces of the Bee Gees in the ’60s, when most everything they did was drenched in overwhelming, almost deranged melancholy, though High Llamas, while not averse to poignancy, never once tip into sentimentality. There’s also a wryness to the closing sound effect of a car hurriedly speeding off – what’s your hurry, Dutchman?

And so to the Escher staircase melody of Giddy and Gay, which has more layers than the Earth’s crust. A forthright organ is the song’s motor, yet more harmonies wonder at the “perfect sunset” and strings offer a wordless, five-note refrain which could get heads swaying at Traitors’ Gate. They have sinister siblings lower in the mix which climb so high that they almost require the invention of a new scale – and even get to kick the whole album off with their own opening track, Giddy Strings – while an almost imperceptible guitar tremolos tremulously and shows Duane Eddy a world he could only have dreamed of.

Checking In, Checking Out gathered respectable – if that’s the word I want and it probably isn’t – as a single, not only in its natural habitat of Mark Radcliffe and Marc ‘Lard’ Riley’s nightime Radio 1 show (my constant companion on hundreds of solitary East Lothian nights in the mid-90s) but also earlier in the day on a station busily establishing its laudable, albeit dogmatic, New Music First policy but still retaining traces of its recent, considerably less radical, past. With its spindly piano and acoustic guitar interplay and its sunburst bridge, it was easily comely enough to draw in listeners yearning for a return to the days of “pure quality” but the breaking-point tension O’Hagan produces on his climactic solo and the curious art installation of “dodgy sculptured licence plates” leave little doubt that the landscape of Gideon Gaye is no place for satin bomber jackets.

Landscaping of a different kind figures on The Goat Looks On, a title we should all give thanks for and a song easily worthy of it. A horrified account of disastrous planning decisions (“A supermarket on the hill/The way things happen makes you feel ill”) and the roughshod approach of those who take such decisions (“I’ll take your money, make it good/Take it to another neighbourhood”) set to the richest sound on the album, utterly belying is low-key origins. It does everything you hope a song like this would – it floats, chimes, gasps, swoops, then climaxes with the rhythm, as tethered as the goat itself, galloping for freedom, though the escape seems doomed.

Probably the most controversial song on Gideon Gaye is Track Goes By, not so much for its 14-minute length as for the manner of its going, a coda lasting well over half the song’s length which consists of sustained repetition of a six-note figure, garnished by flourishes of flute evoking Slim Slow Slider from Astral Weeks. On first listen, the title seems too apt – by the third or fourth, while this may linger, and the song may be more suited to the eight or so minutes it’s been known to be given live, it’s accompanied by a sense that the length is essential to make complete our visit to this place of dreamers, loners, artists, bureaucrats and assorted enigmatic animals.

It was, and remains, a triumph for Sean O’Hagan and his associates. It was probably too refined to have made much headway against Definitely Maybe or Parklife but, along with Portishead’s Dummy, it was the real herald of a belated start in earnest to a decade which had begun disastrously with a surfeit of Stone Roses, Nirvana and Wonder Stuff photocopies being taken seriously as contenders, rather than told to sit back down and eat their greens. It can offer a fresh perspective on this oddest of decades and help you to see its best side – not its worst (PG).

(A) HAWAII (1996)

One of the more curious entries listed in the original ‘Perfect Collection’ was ‘Discover America’ by Van Dyke Parks. Parks is of course the musical genius who worked with Brian Wilson on The Beach Boys’ ‘Smile’ project, his legacy immortalised by the salvaged fruit of that aborted collaboration, songs such as ‘Heroes & Villains’ and ‘Surfs Up’ now universally recognised as amongst the band’s greatest ever achievements. ‘Discover America’, although not the first VDP solo outing, is a very strange album indeed. Originally released in 1972, it was recorded with members of Little Feat and a Trinidadian Steel Band, largely in a bizarre calypso style. I imagine Sean O’Hagan the founder, composer and leader of The High Llamas to be very fond of it. The Llamas’ second full length album ‘Hawaii’ was released 20 years ago this week, and while the two records cannot really be equated stylistically, nevertheless the way they were conceived is not dissimilar, both being highly idiosyncratic panoptic musical odysseys.

One of the more curious entries listed in the original ‘Perfect Collection’ was ‘Discover America’ by Van Dyke Parks. Parks is of course the musical genius who worked with Brian Wilson on The Beach Boys’ ‘Smile’ project, his legacy immortalised by the salvaged fruit of that aborted collaboration, songs such as ‘Heroes & Villains’ and ‘Surfs Up’ now universally recognised as amongst the band’s greatest ever achievements. ‘Discover America’, although not the first VDP solo outing, is a very strange album indeed. Originally released in 1972, it was recorded with members of Little Feat and a Trinidadian Steel Band, largely in a bizarre calypso style. I imagine Sean O’Hagan the founder, composer and leader of The High Llamas to be very fond of it. The Llamas’ second full length album ‘Hawaii’ was released 20 years ago this week, and while the two records cannot really be equated stylistically, nevertheless the way they were conceived is not dissimilar, both being highly idiosyncratic panoptic musical odysseys.

Clocking in at over 76 minutes and featuring 29 tracks (although around ten or so serve as seams between the songs) ‘Hawaii’ was a hugely ambitious project, a sun-drenched compendium of chamber pop, bossa nova, sweeping Fordian (John, not Henry) Americana, pacific bluegrass, old-style waltzes, and Morricone inspired exotica, all glued together by bleary string passages and fragments of space-age electronica, reminiscent of O’Hagan’s synchronous work with Stereolab. The album is best listened to in its entirety; and does not lend itself particularly well to an iPod shuffle. Someone once remarked that if the tracks were rearranged on The Band’s second (eponymously titled) LP, it would be like jumbling up the chapters of a great novel. Well, the rupture to continuity would be similar with ‘Hawaii’, which – while on the subject of The Band – even features a nod to the pine forest wooziness of John Simon’s production, on the marvellously evocative ‘Pilgrims’.

If ‘Sparkle Up’ reminds me – in the best possible way – of the music from both the ITV soap Crossroads and Monty Norman’s Bond theme, then the swooning grace of ‘Literature Is Fluff’ calls to mind the soundtracks to Fellini’s ‘Juliet Of The Spirits’ and ‘La Dolce Vita’, with psych guitar buried beneath a swathe of baroque harpsichord and strings. Both ‘Peppy’ and the single ‘Nomads’ are pushed along by jaunty banjo and brass, while the wistful flute of ‘Cuckoo’s Out’ owes a nod to the dusky late summer languor of Joe Boyd’s production on ‘Bryter Layter’.

‘Doo Wop Property’ and ‘Island People’ once again showcase those strings which seem to yearn for a romantic return to a lost (gentler) golden age of America with as much nostalgia as Welles did in ‘The Magnificent Ambersons’. ‘The Hokey Curator’ is short but unbearably beautiful, containing a melting chord sequence ravishing enough to give Burt Bacharach sleepless nights.

The closest thing to a centre-piece on the album is perhaps ‘Ill-fitting Suits’, a truly sublime piano piece with slumberous meandering vibraphone, big kisses of brass punctuated with pizzicato, and washes of brooding cello – it makes a welcome reappearance as an instrumental reprise to the album. ‘Dressing Up The Old Dakota’ twists on the last flat note of the verses, giving new impetus to the beginning of each of the following ones, until from the mid-way point the string section and the old ivories get locked in a gloriously discordant tug-of-war. Meanwhile ‘Theatreland’ sounds more contemporary and conventional, the closest O’Hagan gets here to here to revisiting the sound of Microdisney, and ‘Campers In Control’ is R&B a la Llamas with its rising doo-wop rhythm given a shimmering makeover with harmonies befitting the late 60s sunshine pop of The Turtles or The Association. The musicianship throughout is superb, the arrangements beautifully measured, and for that much of the credit should be shared with multi-instrumentalist Marcus Holdaway, whom O’Hagan has credited as “the best musician I have ever encountered [who] has totally visualised the way I work.”

It has been a continual source of frustration for O’Hagan that his music is reduced to something akin to a facsimile of that which The Beach Boys produced between 1966-73. It is unquestionably much more than that. ‘Hawaii’ effortlessly transcends the perennial accusation that it is little more than an omnibus edition of ‘Friends’ or ‘Holland’, being sufficiently capacious to incorporate a veritable potpourri of influences. Speaking to TNPC, O’Hagan recalls: “The critics at the time simply could not keep up. They had no idea where we were going with these influences. There were plenty of British cinema references, a bit too of Gene Clark’s odd floundering LA Sessions, Nina Rota, Bernard Herman, Mingus. No critic heard any of this, even though the clues were jumping up and waving red flags!”

Nevertheless, ‘Hawaii’ is an album which brought O’Hagan close to a commission to co-create with Brian Wilson a Beach Boys reunion album in the late 1990s. Sean’s brief encounter with the band might read as pure comedy gold (http://uncanny1.blogspot.co.uk/2005/05/brian-wilsonandy-paleysean-ohagan.html?m=1) but one imagines for O’Hagan himself, the humblest of souls, it must have been a most disquieting experience, cathartic even – and certainly, post-Hawaii, the influence of Wilson & co. seemed to be with each subsequent release, ever less discernible.

The High Llamas never make Top 100 Albums lists, but to those that love their music, O’Hagan is quite simply a musical genius. He is sometimes unfairly criticised for a penchant for slipping all too comfortably into easy listening territory and also for his lyrical obtuseness. As regards the former point, well some people are simply too much the children of 1977 to make allowance for that. As for the lyrics, some have suggested he has cloistered his soul away – taciturn by nature, he seems unwilling to make his music a forum for wrestling with the complexities of existence; some that his rather abstract observations are designed so as not to detract from the sumptuousness of the music, a strategy followed by others such as The Cocteau Twins (few complained of their lyrical ‘deficiencies’). Not so. It is important to remember that O’Hagan’s first songwriting partner was Cathal Coughlan, highly literate, fiercely intelligent, “a writer of such originality and strength, my teacher”. O’Hagan has consciously steered away from writing anything which could be considered emotionally trite in his lyrics, most pop songs being for him “a string of cliche”, and while he acknowledges his own limitations, he has sought refuge and inspiration in the rich poetic strain of wordsmiths such as Parks, Dylan and Will Oldham.

And so there is a playfulness to the writing which, rather than invite a personal emotional response from the listener, invites us rather to conjure in our minds specific scenes in the imaginary lives of the songs’ protagonists: (“Take care to avoid the heavy stuff/I give up, this literature is fluff/Trawled through sketches of notes the night before/Chased the baffled employess floor to floor/Hung a ‘do not disturb’ on glass swing doors.”) This is a writer who clearly loves words as much as music, but words of love he shall not write. In their place, he documents the mini dramas of an amateur theatre company unfolding on a creaking old stage or observes a military operation undertaken to cordon off hotel grounds – we listen intently, sufficiently detached from the humdrum of their activities to enable us to create our own little mental retreat, a supine sanctum of uncommonly blissful sound. If ever there was a disc made for a desert island then this is it. (JJ)

Can a troubled artist create great art? Not according to Van Morrison, who once claimed that ‘you’ve got to be happy’ to produce your best work. But Van himself sounded like a man in pain when he made the majestic ‘Astral Weeks’, and there is certainly a counter argument to his assertion. Consider for example, Sly’s fractured and frazzled ‘There’s A Riot Goin’ On’, Dylan’s post-marital post mortem ‘Blood On The Tracks’, the austere desolation of Nick Drake’s ‘Pink Moon‘ or the neurotic but bleakly transcendent ‘Sister Lovers’ by Big Star – astonishing albums created under great psychological duress. You may wish to add to that impressive little list ‘New York Tendaberry’, Laura Nyro’s stark but affecting masterpiece from 1969.

Can a troubled artist create great art? Not according to Van Morrison, who once claimed that ‘you’ve got to be happy’ to produce your best work. But Van himself sounded like a man in pain when he made the majestic ‘Astral Weeks’, and there is certainly a counter argument to his assertion. Consider for example, Sly’s fractured and frazzled ‘There’s A Riot Goin’ On’, Dylan’s post-marital post mortem ‘Blood On The Tracks’, the austere desolation of Nick Drake’s ‘Pink Moon‘ or the neurotic but bleakly transcendent ‘Sister Lovers’ by Big Star – astonishing albums created under great psychological duress. You may wish to add to that impressive little list ‘New York Tendaberry’, Laura Nyro’s stark but affecting masterpiece from 1969.

The customary Liner Notes of the 1960s and early 1970s album demonstrated little variation. Usually they were insipid, vain attempts by unfeasibly witless record companies to promote their artists (Check out the US ‘Meet The Beatles’ issue: ‘You’ve read about them in Time, Newsweek, The New York Times. Here’s the big beat sound of the fantastic phenomenal foursome. A year ago the Beatles were known only to patrons of Liverpool pubs. Today there isn’t a Britisher who doesn’t know their names…’) Occasionally some aspired to be more meaningful or poetic, although sometimes pretentiously so. For The Beach Boys ‘Sunflower’ album however, a novel approach. Neither witty nor poetic, they serve a quite different purpose. Forgive me for reprinting them in their entirety:

The customary Liner Notes of the 1960s and early 1970s album demonstrated little variation. Usually they were insipid, vain attempts by unfeasibly witless record companies to promote their artists (Check out the US ‘Meet The Beatles’ issue: ‘You’ve read about them in Time, Newsweek, The New York Times. Here’s the big beat sound of the fantastic phenomenal foursome. A year ago the Beatles were known only to patrons of Liverpool pubs. Today there isn’t a Britisher who doesn’t know their names…’) Occasionally some aspired to be more meaningful or poetic, although sometimes pretentiously so. For The Beach Boys ‘Sunflower’ album however, a novel approach. Neither witty nor poetic, they serve a quite different purpose. Forgive me for reprinting them in their entirety: