I was never much of a Zappa fan – for me, ‘Freak Out’ was as good as it got – but I must give Frank some credit for overseeing the formation of Straight Records. It’s small catalogue of only 16 albums and a handful of 45s is amongst the most wildly eclectic distributed by any record label. Initially, Zappa envisaged Straight as an outlet for more mainstream artists, allowing it’s partner label Bizarre to focus on experimental/oddball LPs by the likes of Lenny Bruce, Wild Man Fischer and Frank himself. But somewhere along the line the script got mixed up. That the likes of ‘Trout Mask Replica’ and Tim Buckley’s ‘Starsailor’ ended up on Straight and not on Bizarre, seems to indicate that, despite honourable intentions, there was no distinguishable musical demarcation between the labels. It is nigh on impossible to imagine two LPs more audaciously ‘off the wall’ than those two.

I was never much of a Zappa fan – for me, ‘Freak Out’ was as good as it got – but I must give Frank some credit for overseeing the formation of Straight Records. It’s small catalogue of only 16 albums and a handful of 45s is amongst the most wildly eclectic distributed by any record label. Initially, Zappa envisaged Straight as an outlet for more mainstream artists, allowing it’s partner label Bizarre to focus on experimental/oddball LPs by the likes of Lenny Bruce, Wild Man Fischer and Frank himself. But somewhere along the line the script got mixed up. That the likes of ‘Trout Mask Replica’ and Tim Buckley’s ‘Starsailor’ ended up on Straight and not on Bizarre, seems to indicate that, despite honourable intentions, there was no distinguishable musical demarcation between the labels. It is nigh on impossible to imagine two LPs more audaciously ‘off the wall’ than those two.

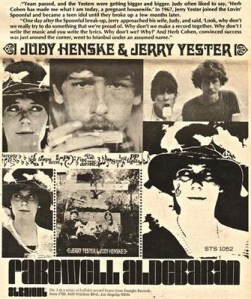

Which brings us to Jerry Yester and Judy Henske’s ‘Farewell Aldebaran’, released on June 16th 1969, the same day as Beefheart’s magnum opus ‘Trout Mask Replica’ (catalogue numbers STS-1052 and STS-1053 respectively). The latter, regarded by many as the greatest and most adventurous album in rock history, has a far more enduring legacy than it’s comparatively neglected twin. In its own way however, ‘Farewell Aldebaran’ is as peculiarly eccentric: it is a brave record, not at all easy to fall in love with, and yet an utterly unique and compelling listen from start to finish. It is not strange in the same way that TMR is ‘strange’. TMR, if it sounds wholly impenetrable to some, has a singular vision which might defy easy categorisation, but it’s mixture of free jazz, wild delta blues and ecological concerns gives it a recognisable thematic unity. Not so ‘Aldebaran’, which has an insatiable eclecticism that makes it in many ways an even more challenging listen. It has oft been likened to one of those old record label sampler compilations – ten bands, ten very different sounds – but while this is a convenient analogy to draw, it is a little off the mark. It isn’t ten bands, just Jerry, Judy and a small host of guest musician friends. And if the album has an identity crisis, there are still patterns and motifs which lend it it’s own distinctive aura.

‘Snowblind’, a creeping bluesy howler with a fizzing lead guitar, finds Henske returning from the wilderness years of cabaret performance, wailing her heart out like Janis Joplin with some obliquely gothic lyrics: [‘Fallbrook Sedgewynd gave to Nancy/ringnecks for her coachmen’s fancy/Eggs and emeralds, shocking garters/Devilled prunes to stop and start her/Nancy gave to Fallbrook Sedgewynd/neither nods nor time of day/Love is nasty, love is so blind/Love shall make us all go snowblind.’] Upon closer inspection, it could be a proto-glam stomp, and stands in stark contrast to ‘Horses On A Stick’, a slice of pure bubblegum sunshine pop, reminiscent of The Association (Yester had produced some of their albums) or The Turtles.

After that schizophrenic pairing there are a few songs which are closer cousins, featuring both harpsichord and a theatrical vocal performance from Henske. ‘Lullaby’, sung beautifully in a vulnerable quiver, is a darkly melodramatic way to sing one’s child to sleep [‘The end of the world is a windy place/Where the eagle builds her nest of lace/I rock you asleep in the cradle of end/Listen, baby, to the wind’], while Judy’s instinctive comedic impulse gets an airing on ‘St. Nicholas Hall’. Over some bizarre background overdubs, her vocal reaches a near hysterical crescendo during this fiercely satirical attack on the Church [‘Blessed are the pure in heart

(We need a new organ by June)

Blessed are the merciful

(The old one’s badly out of tune)

Blessed are the peacemakers

(Please send us the money soon)

Sincerely yours in Jesus/Your Dean’]

Vocal duties are shared on ‘Three Ravens’, one of two gorgeous psych-baroque outings telling tales of knights and maidens and featuring a string arrangement worthy of his friend, the late Curt Boettcher (Sagittarius, The Millenium). It wouldn’t sound out of place on a Left Banke album or even The Zombies genre-defining ‘Odessey & Oracle’. The final coda is sublime making it truly a song to treasure. The other, ‘Charity’, is glorious – it’s folksy guitar might recall once again The Association (specifically their ‘Goodbye Columbus’ soundtrack), but it’s orgiastic organ-driven ending is a masterstroke.

The lengthiest track on the album, ‘Raider’, is the strangest of brews, featuring bow banjo and fiddle, both unceremoniously knocked askew by a clunking harpsichord – if one can imagine a buoyant bluegrass version of the theme for The Ipcress File – a toe tapping knee-slapping classic with great harmonising at the finale. It’s followed by the album’s one weak point – the hazy jazz inflections of ‘Mrs. Connor’ mean it’s the only moment that feels contrived here. The rest of the album if stylistically disparate, manages somehow to feel remarkably organic.

Judy’s strident matronly vocal returns on ‘Rapture’ which once again is unashamedly poetic

[‘Lovers who lie/beneath the night sky/neither speak nor hear/in the perfect stillness/She is near/Her voice in the heart’s blood comes roaring/In rapture they die’] It features a wheezing harmonica and introduces some Moog (but understated, cunningly rehearsing it’s centre-stage performance on the closing title track), all embellished by strange echo-layered vocal overdubs not entirely dissimilar to engineer Herb Cohen’s work on the aforementioned ‘Starsailor’.

Perhaps producing albums such as ‘Happy Sad’ by a star dancer such as Tim Buckley had opened up new vistas for Yester. The curtain comes down with the staggeringly ambitious title track, where he leaves his Lovin’ Spoonful days for dead with what is undoubtedly one of the very strangest songs of the 1960s. [‘See, she is descending now/Starting the slide/The comets cling to her/The fiery bride/She is the mother of/The mark and the prize/The glaze of paradise/is in her eyes/Her mouth is torn with stars/and brushed with wings/She cannot call to us/She does not sing.’] It’s so ‘out there’, at times I find it near excruciating – a mindbending space Moog prog monstrosity. When those Dalek vocal treatments gatecrash the party you’ll know what I mean. But for all it’s crazed nonsense, on most days I love it to bits. It’s the one moment on the album where Yester sounds possessed. Now there were stars – or perhaps asteroids – in his eyes.

I first read about ‘Farewell Aldebaran’ in Strange Things Are Happening, a brilliantly niche retro rock magazine active (pre-Mojo) between 1988-90. One issue contained a feature on Straight Records. I was intrigued, but tracking down the album proved elusive until I hit the jackpot at a record fair in 1993. At the same event I acquired two other Straight releases, Tim Dawe’s ‘Penrod’ and Jeff Simmons’ ‘Lucille Has Messed My Mind Up’. Collectively, this set me back about £50, a costly business, particularly as ‘Aldebaran’ was the only one of the three with which I was in any way smitten. I’ve long since parted company with the other two, but the music on ‘Farewell Aldebaran’ was different, bursting with ideas, brazenly ambitious, rich in gothic poetry, subtly sublime one moment and hysterically overbearing the next. It had one foot in the past and one in the future, and was maddeningly difficult to pin down…the kind of album you make your own, because you know no-one else is listening. Every collection – yours included – needs a few of those. (JJ)

The subconscious mind is a powerful entity. When I listen to ‘Hollywood’ the opening track on Cluster’s ‘Zuckerzeit’ LP, I can envisage it serving as a fitting theme tune for the BBC TV series ‘Tomorrow’s World’, studio presenter Raymond Baxter enthusiastically leaning over Dieter Moebius and Hans-Joachim Roedelius, to point out the latest technical features of their electronic equipment with his trusty Parker pen. I am then reminded that this ‘vision’ was actualised by Kraftwerk on TW in 1975. I have little recollection of their appearance on the programme. I suspect it must be a vague memory buried deep inside my subconscious since childhood. Nevertheless, one can only imagine how far ahead of its time ‘Hollywood’, might have sounded in 1974. While it’s synthetic drum patterns deliver an irregular asthmatic beat (like Mylar punctured with a razor), those synth lines begin discretely, buried low in the mix, suddenly springing to life in darting oscillating arcs of sound – like aliens weeping. If it is one of Krautrock’s most perfectly realised moments, ‘Zuckerzeit’ as a whole is one of the genre’s least typical albums. Perhaps rather, it is the sound of aliens laughing.

The subconscious mind is a powerful entity. When I listen to ‘Hollywood’ the opening track on Cluster’s ‘Zuckerzeit’ LP, I can envisage it serving as a fitting theme tune for the BBC TV series ‘Tomorrow’s World’, studio presenter Raymond Baxter enthusiastically leaning over Dieter Moebius and Hans-Joachim Roedelius, to point out the latest technical features of their electronic equipment with his trusty Parker pen. I am then reminded that this ‘vision’ was actualised by Kraftwerk on TW in 1975. I have little recollection of their appearance on the programme. I suspect it must be a vague memory buried deep inside my subconscious since childhood. Nevertheless, one can only imagine how far ahead of its time ‘Hollywood’, might have sounded in 1974. While it’s synthetic drum patterns deliver an irregular asthmatic beat (like Mylar punctured with a razor), those synth lines begin discretely, buried low in the mix, suddenly springing to life in darting oscillating arcs of sound – like aliens weeping. If it is one of Krautrock’s most perfectly realised moments, ‘Zuckerzeit’ as a whole is one of the genre’s least typical albums. Perhaps rather, it is the sound of aliens laughing. The customary Liner Notes of the 1960s and early 1970s album demonstrated little variation. Usually they were insipid, vain attempts by unfeasibly witless record companies to promote their artists (Check out the US ‘Meet The Beatles’ issue: ‘You’ve read about them in Time, Newsweek, The New York Times. Here’s the big beat sound of the fantastic phenomenal foursome. A year ago the Beatles were known only to patrons of Liverpool pubs. Today there isn’t a Britisher who doesn’t know their names…’) Occasionally some aspired to be more meaningful or poetic, although sometimes pretentiously so. For The Beach Boys ‘Sunflower’ album however, a novel approach. Neither witty nor poetic, they serve a quite different purpose. Forgive me for reprinting them in their entirety:

The customary Liner Notes of the 1960s and early 1970s album demonstrated little variation. Usually they were insipid, vain attempts by unfeasibly witless record companies to promote their artists (Check out the US ‘Meet The Beatles’ issue: ‘You’ve read about them in Time, Newsweek, The New York Times. Here’s the big beat sound of the fantastic phenomenal foursome. A year ago the Beatles were known only to patrons of Liverpool pubs. Today there isn’t a Britisher who doesn’t know their names…’) Occasionally some aspired to be more meaningful or poetic, although sometimes pretentiously so. For The Beach Boys ‘Sunflower’ album however, a novel approach. Neither witty nor poetic, they serve a quite different purpose. Forgive me for reprinting them in their entirety: